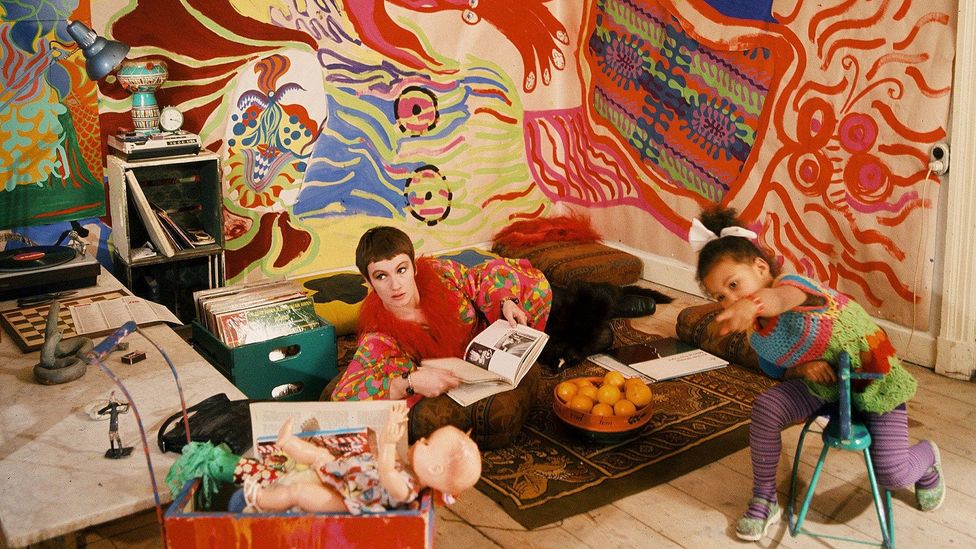

(Image credit: Sven Asberg/ Courtesy of Estate of Moki Cherry)

Moki Cherry blended work and life, embodying a free-spirited 1970s vision – and her legacy lives on. Her daughter, the singer-songwriter Neneh Cherry, and her granddaughter Naima Karlsson recall her life and work.

I

In a photograph from 1967, the Swedish artist Moki Cherry lies on a rug on the floor in her home, staring into the distance, sporting a feather-trimmed jacket and a pixie haircut. She holds a book open on a page seemingly about art. Behind her, the walls are entirely draped in decorated textiles covered in colourful shapes and patterns – the ambiguous body parts and abstract swirling lines of these pieces have since become known as the artist’s signature style. In front of her is her young daughter, the now multi-award-winning singer-songwriter Neneh Cherry, sitting on a stool and pointing in the direction Moki is staring.

More like this:

– Still the most dangerous woman in art?

– Seven striking images of Africa’s new wave

– Why the boho rock goddess aesthetic lives on

This image encapsulates Moki as an artist, and how Neneh perceives her mother. “She was self-taught but also incredibly studious,” the now 59-year-old Neneh tells the BBC over the phone, reflecting on her childhood. Neneh notes that Moki was always working to improve her practice. “She was always present, but there was a kind of intensity to it that was so beautiful,” she says. “I remember her working with fabrics on the floor. I always think of how her head was turned down on whatever area she was working on.”

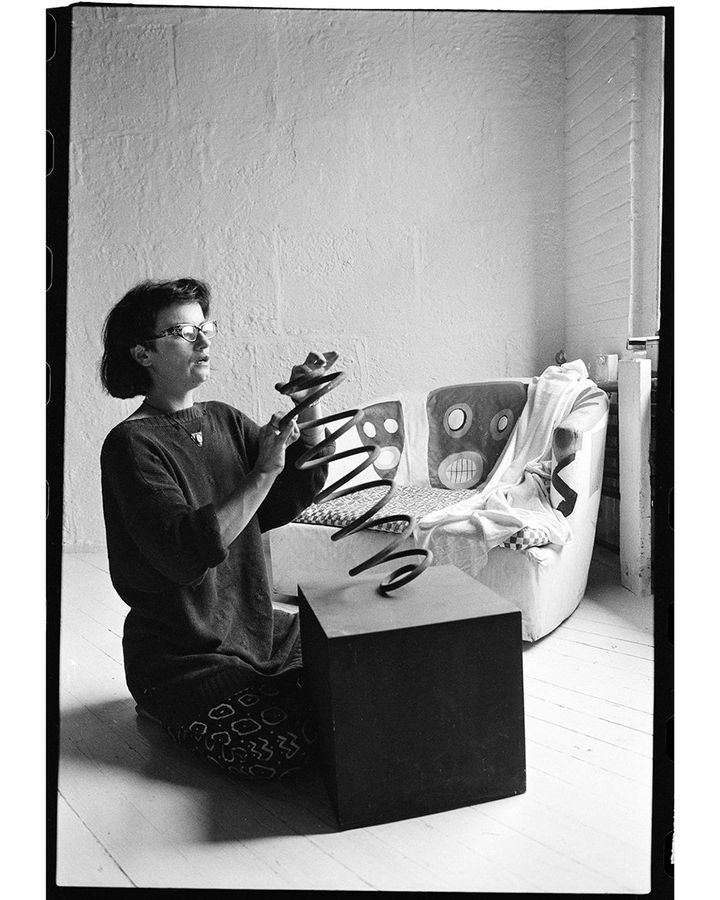

Cherry – pictured with her artworks in the 1980s – explored various mediums including ceramics, collage and tapestry (Credit: Courtesy of Cherry archive)

Moki was an interdisciplinary artist born in 1943 in Norrbotten, a region in the far northeast of Sweden. She created art from the 1960s until she died in 2009, exploring various mediums, including tapestry, fashion, painting, collage and ceramics. Despite her name being relatively unknown throughout her life, “Moki’s work is more well-known now,” says Elisabeth Millqvist, director of Moderna Museet in Malmö, Sweden, where Moki Cherry: A Journey Eternal, the most extensive retrospective of her art, is on show until March 2024.

Moki’s creations graced everything from musician costumes to her family’s everyday clothes, to album covers and the backdrop of music concerts, most notably those of her partner, the American jazz trumpeter Don Cherry, who she met in the mid-1960s and collaborated with for decades. “Her work is very much organic in how it can be presented,” adds Andreas Nilsson, who co-curated the show in Malmö with Millqvist. “She made it not only to present it in a white-cube gallery as we are doing here, but also for concerts, clothes and theatre stages.”

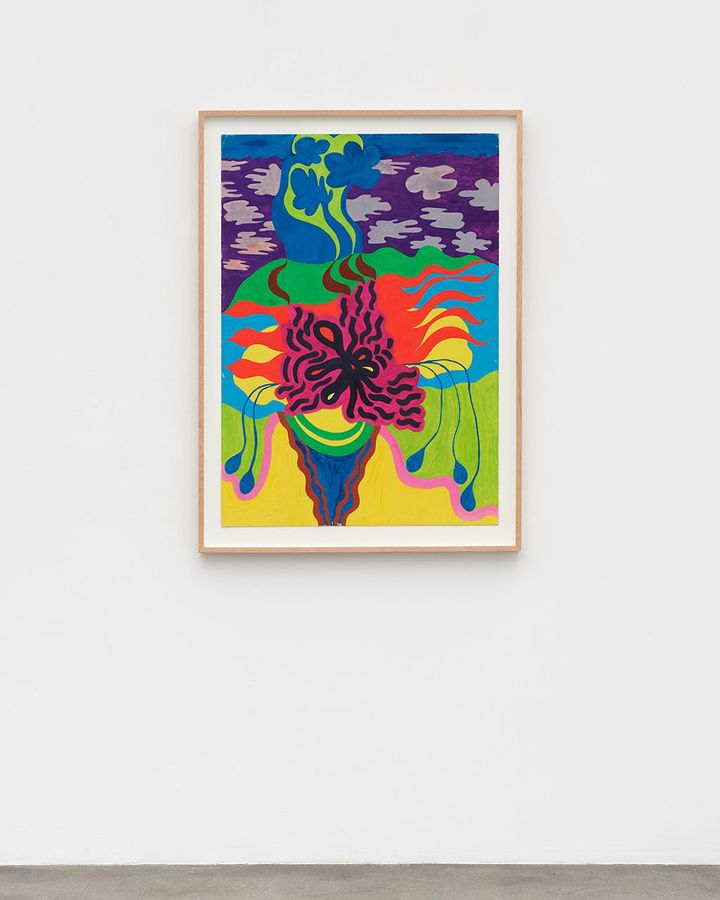

Dragon by Moki Cherry – nature and Buddhism were among the artist’s inspirations (Credit: Nicolai Wallner)

A resurgence of interest in tapestry and the acceptance of it as an art form have resulted in Moki and her work, which many have deemed ahead of its time, gaining more recognition. It has been shown across the globe, including at Moki Cherry: Here and Now at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art last summer, which was co-curated by Naima Karlsson, Moki’s granddaughter. “So many contemporary artists are using textiles and ceramics, which is great, but it’s not that long ago that galleries did not take that kind of work seriously, and saw it as women’s hobbies,” 40-year-old Karlsson, who administers Moki’s estate, tells the BBC. “I think she stood by the materials she was interested in but struggled to find many people keen on showing that in galleries.” Other solo exhibitions of Moki Cherry’s work have taken place at Galleri Nicolai Wallner in Copenhagen, and Argos in Brussels in 2022, and at Corbett vs Dempsey in Chicago in 2021.

The stage as home

Part of what stands out about Moki as an artist is what she and her work stood for, and how she balanced various aspects of her existence. She lived by a simple motto: “The stage as home, and the home as a stage,” which highlights not only how she saw her life as very much intertwined with her practice but also how she navigated motherhood in the 1960s and 70s, bringing up her two children Neneh and Eagle-Eye.

Cherry melded the human figure with animal shapes and elements from nature, creating a psychedelic mood (Credit: Nicolai Wallner)

According to curators Millqvist and Nilsson, the rise of women’s rights in the US in the 1960s and 70s, where Moki and her partner Don were living at the time (as well as in Sweden), meant working women were becoming increasingly accepted. Gender roles in the home were still prevalent, though Moki challenged these conventions through her art. “She looked for a way to make the domestic situation an artistic one, and household chores into artworks,” says Millqvist, noting that Moki and Don’s home often became an extension of their practice and a creative hub where she and Don invited children and artists from the community to make things.

Neneh also recalls how Moki often set up her studio space to accommodate work and motherhood. “On some tables, there could be an artwork she was working on depending on what she was doing, whether it was fabric or on paper or whatever, and then in the corner, there would be a stack of pillowcases she was ironing,” Neneh says. “There was a duality Moki fought with: the dream of wanting a home that functioned but also finding the time to do her work.” That said, Neneh notes that her mother appeared to embrace some elements of traditional systems, which Neneh suggests came from Moki valuing aspects of her Swedish upbringing, resulting in her enjoying activities such as “the slow cooking process of making food”.

Music was central to the Moki’s work, and she frequently collaborated with her partner Don Cherry, a US jazz musician (Credit: Courtesy of Nottingham Cotemporary)

But, alongside subverting ideas of motherhood, Moki made works unique to her personality and interests, especially nature and Buddhism. “I often think about walking down the street with my mother where we used to live in New York,” Neneh says. “There was some kind of weird weed growing in a crack in the concrete, and she was like, ‘Wow, look at that. Look at how powerful nature is.” Consequently, Moki’s work often melds the human figure, various animals and the environment to a point where it’s difficult to decipher one aspect of the piece from another. “It’s like those images that you turn upside down and see different shapes,” Millqvist says. “Depending on how you look at it, it could be the sea or a hand.”

The home as stage

Spiritual and historical symbols are also prevalent in Moki’s work. “One of the most apparent ones is her use of snakes, which appear in all different areas of her work,” Karlsson explains. “Snakes are a prominent and ancient symbol in many different places [across the globe] that can signify something connected to nature or women’s spirituality.” Karlsson particularly points out the ouroboros (or uroboros), an ancient symbol depicting a snake eating its own tail, “which can represent the ongoing continuation of life and death,” Karlsson explains. Hands also consistently appear in Moki’s work, which could relate to the use of mudra (or hand positions) in Buddhism, which Moki practised. In Buddhist art, different hand positions represent particular meanings. Her piece Spirit, 1976 shows green hands going up each side of her textile appliqué with fingers in certain gestures, which could be interpreted as specific mudras depending on how the viewer perceives the fingers.

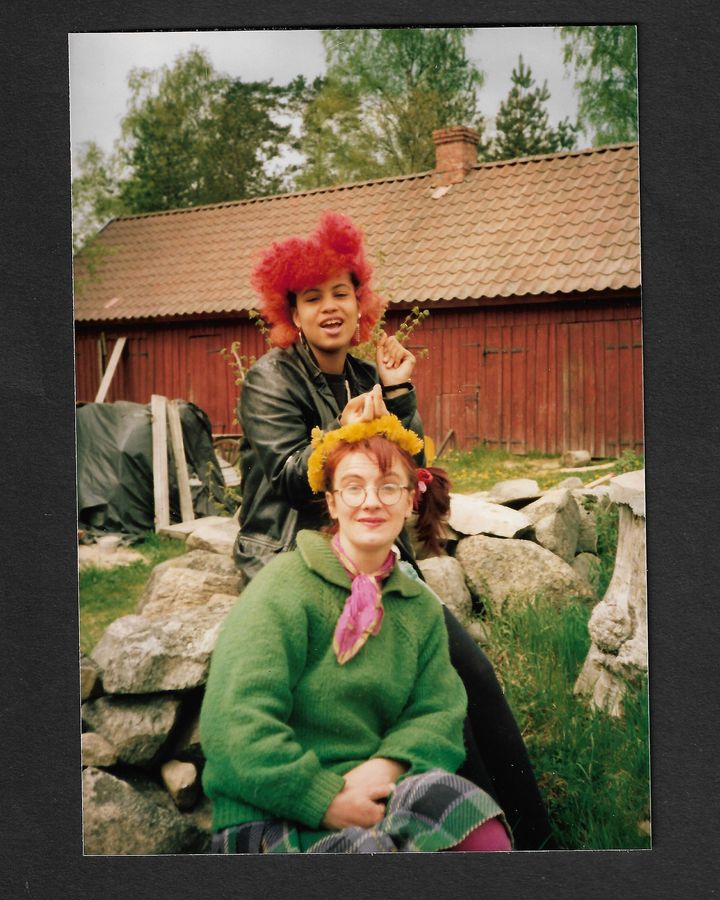

Moki and her daughter Neneh Cherry in the late 1970s – Neneh and her daughters are now all musical artists (Credit: Courtesy of Cherry archive/ Estate of Moki Cherry)

Both musicians, Neneh and Karlsson note that Moki instilled a sense of curiosity about the world and a need for creativity in her family. “She had no interest in wanting to be a stereotypical domestic person. But at the same time, she was very interested in rebuilding the idea of what home meant in a soulful way,” says Neneh, who started her music career in London in the early 1980s, where she performed in punk and post-punk bands, including The Slits and the experimental Rip Rig + Panic. “I definitely feel I’ve continued with that,” Neneh says of Moki’s approach to both art and homelife. Karlsson, Neneh’s daughter, incorporates photography, drawing, text and music in her practice. Neneh’s other two children – with record producer husband Cameron McVey – Mabel and Tyson McVey, are also musicians, and Mabel won the Best British female solo artist award in 2020. As Neneh puts it: “My kids grew up in the continuation of that environment, and are now making their own versions of that, and it’s very powerful.”

Moki Cherry: A Journey Eternal is at the Moderna Museet in Malmö, Sweden, until 3 March 2024.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.

;