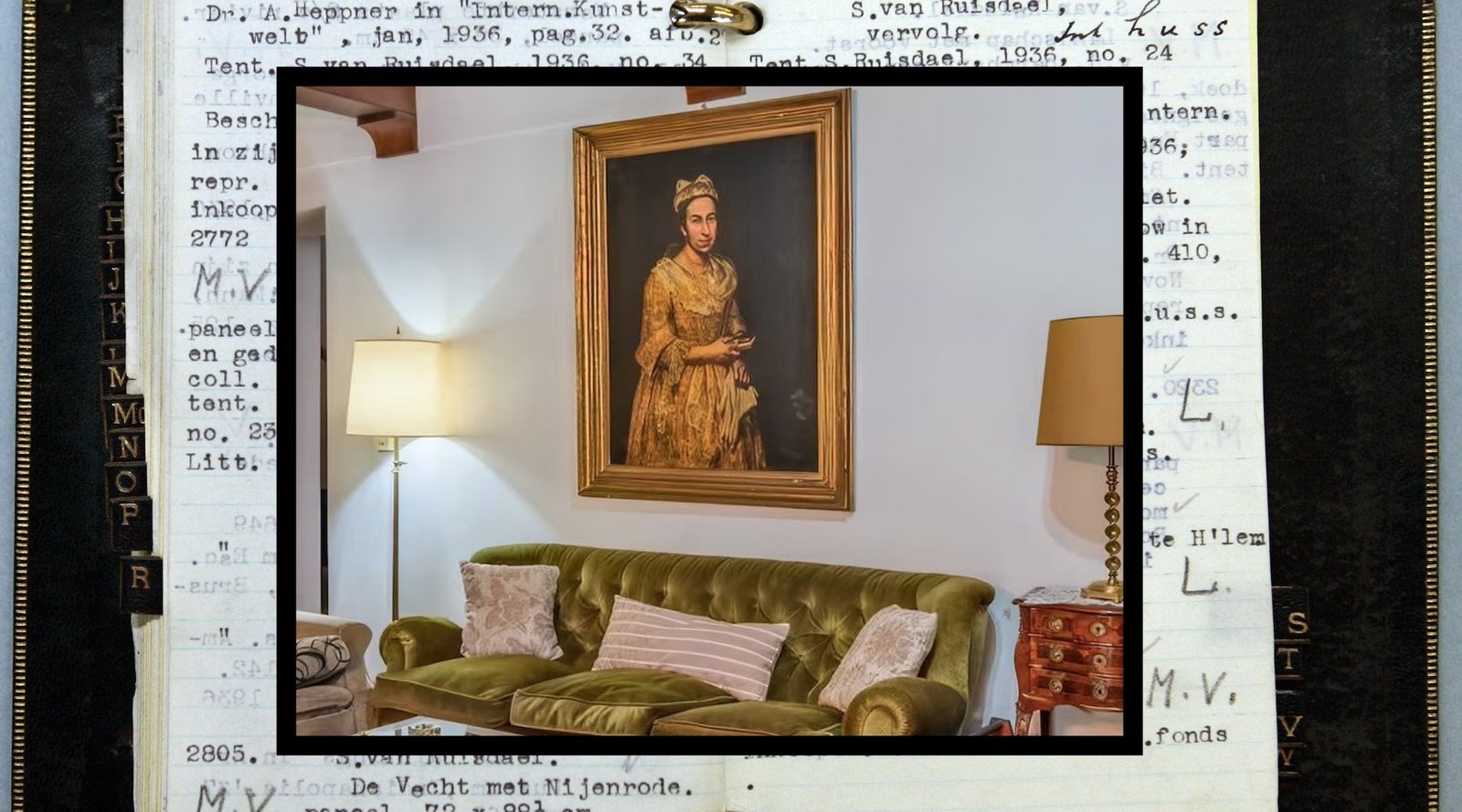

In his study, Alex Kachkine, SM ’23, presents a new method he’s developed that involves printing the restoration on a very thin polymer film that can be carefully aligned with a painting and adhered to it or easily removed. As a demonstration, he used the method to repair a highly damaged 15th-century oil painting he owned. First he used traditional techniques to clean the painting and remove any past restoration efforts. Then he scanned the painting, including the many regions where paint had faded or cracked, and used existing algorithms to create a virtual version of what it may have looked like originally.

Next, Kachkine used software he developed to create a map of regions on the original painting that require infilling, along with the exact colors needed. The method automatically identified 5,612 regions in need of repair and filled them in using 57,314 different shades. This map was then translated into a physical, two-layer mask printed onto polymer-based films. The first layer was printed in color, while the second layer was printed in the exact same pattern but in white.

“In order to fully reproduce color, you need both white and color ink to get the full spectrum,” Kachkine explains. He used high-fidelity commercial inkjets to print the mask’s two layers, which he carefully aligned with the help of computational tools he developed. Then he overlaid them by hand onto the original painting and adhered them with a thin spray of conventional varnish. The films are made from materials that can be easily dissolved in case conservators need to reveal the original, damaged work. The entire process took 3.5 hours, which he estimates is about 66 times faster than traditional restoration methods.

If this method is adopted widely, Kachkine emphasizes, conservators should be involved at every step, to ensure that the final work is in keeping with an artist’s style and intent. The digital file of the mask can also be saved to document exactly what was restored. “Because there’s a digital record of what mask was used, in 100 years, the next time someone is working with this, they’ll have an extremely clear understanding of what was done to the painting,” Kachkine says. “And that’s never really been possible in conservation before.”

The result, he hopes, will be a new lease on life for many works that have not had a chance to be repaired by hand. “There is a lot of damaged art in storage that might never be seen,” he says. “Hopefully with this new method, there’s a chance we’ll see more art.”