(Credits: Far Out / Dani Marroquin)

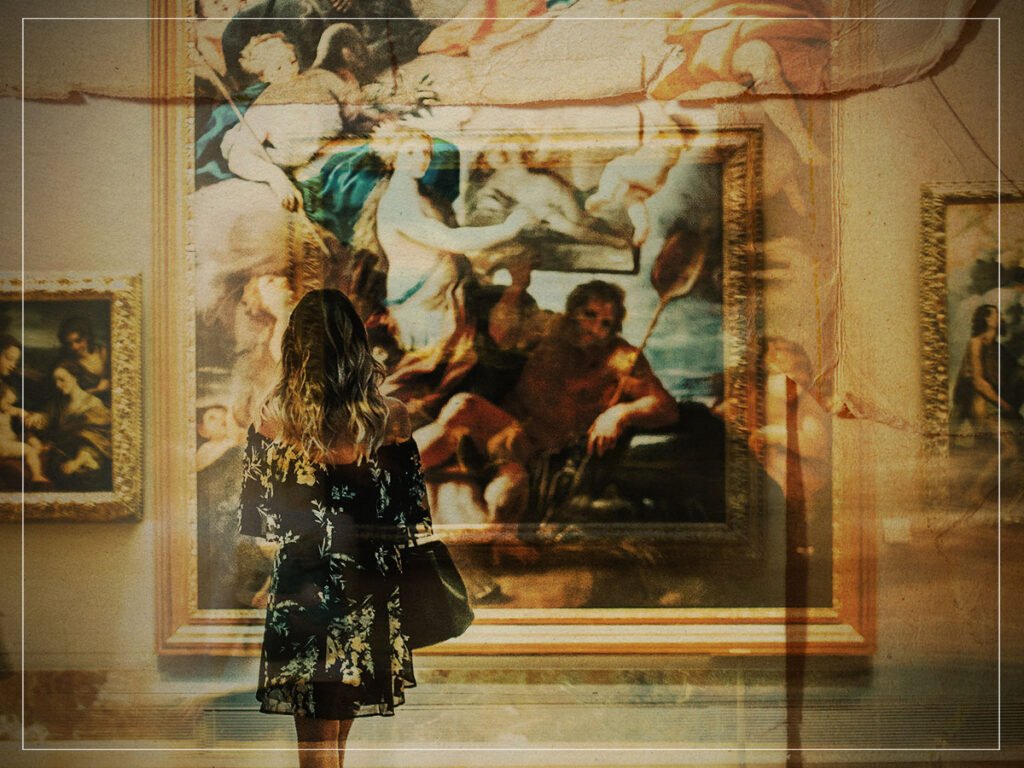

Before I answer this question, let’s take a little history lesson together. The expression “break the fourth wall” has existed in multiple forms of visual arts, primarily in film and painting. Films like Annie Hall, Fight Club, and Amélie all include examples of “breaking the fourth wall” in ways that I won’t get into because this story is about the first painting that broke the fourth wall. However, if you’re too embarrassed to own up to the fact that you’re still not sure what this “fourth wall” I keep banging on about is, then allow me to explain that as well.

In simple terms, the expression refers to a work of art that addresses the viewer in some way. Therefore, it no longer keeps the story within the confinements of a picture frame or a TV screen but steps out of it, takes our hand and pulls us in (all of this metaphorically, of course).

Now, before you start to ask yourself, “Well, what’s the point of this?”; I’ll tell you why. It feels marvellous to be watching a film you’re terribly engrossed in or to be staring at a painting that transports you to another universe, but there’s no fun in that, really.

So, suddenly, out of nowhere, the character in the film you’re watching might stare at you and say something you realise isn’t really part of the plot but hits you deep, or a figure in a painting might be doing something that doesn’t fit but makes sense. These are examples of “breaking the fourth wall”, and they might conjure an unsettling feeling that bursts your bubble of transfixion and brings you back to reality. That’s precisely the point; it’s supposed to make you realise that what you are looking at is merely art.

Such a cool concept was actually not invented recently; it never required any fancy technology or a luminary artist. Believe it or not, back in the 15th century, Renaissance artists really were smashing down that fourth wall, so queue Jan van Eyck.

So, what is the first painting that broke the fourth wall?

Of course, we can’t know for certain the first painting to do this, but art historians have a pretty good idea. The painting in question is called The Arnolfini Portrait by Dutch painter Jan van Eyck. It is a relatively small oil painting, dating back to 1434, depicting what is believed to be the wedding shoot of an Italian merchant, Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and his wife.

The painting is harrowingly clear and confusing all at once. Van Eyck has painted every object, down to the fine silver hairs of the little dog between the couple, so precisely that it looks like it was painted under a microscope by an ant. It’s the butteriness of the green dress, the glistening brass of the chandelier in the light and the red capillaries around the eyes of the merchant that make the painting so palpable.

Like many other Renaissance artists, van Eyck, a master illusionist, was in the race to make the most lifelike painting possible. He did a pretty good job at it; Ernst Gombrich, who wrote one of the art history “Bibles”, described this as “for the first time in history, the artist became the perfect eye-witness in the truest sense of the term”.

If it wasn’t already enough that we feel like we can squeeze the lady’s rosy cheeks from how perfectly bouncy they look, let me draw your attention to something fascinating and slightly creepy. On the wall at the back of the room, bang in the middle between the pair, is a mirror. If you peer close enough, you will see that it reflects what’s happening in the room: the window, the backs of the married pair, and then two unknown figures, a man and a woman.

It is believed that the man is van Eyck himself; the latin quote on the wall that reads “Jan van Eyck was here”, gives it away. But who’s the woman? If van Eyck is present in the picture, then perhaps we, as the viewer in the reflection, are the woman. The convex mirror seems to act as a camera lens that takes a snapshot of the wedding taking place, and van Eyck, as the viewer, places us as witnesses to this important moment.

Suddenly, we are engulfed in a wealthy couple’s bedroom in 15th-century Bruges. Whether we want to be there or not, van Eyck exquisitely draws us into the painting, making us worthy participants. Centuries later, we are able to connect with this painting just as much as van Eyck did when creating it.

Related Topics