When most people think of the artist Jackson Pollock, what comes to mind are his gestural, abstract drip paintings, which are almost synonymous with the male-dominated postwar New York art scene. But before he began making those radical works in about 1943, the artist experimented in expressionist, figurative painting heavily influenced by Pablo Picasso, among others.

“That fucking Picasso,” Pollock famously said. “He’s done everything.” But of course, Pollock would go on to prove himself wrong, developing his own form of expression with paint, which also drew from sources including Native American art, Mexican muralists, and European Surrealists exiled in New York.

Jackson Pollock, The Moon Woman (1942). © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / ADAGP, Paris 2024.

Still, the great Spanish Modernist was a crucial thread running through Pollock’s artistic journey, driving him into ever-more-liberal explorations of figurative abstraction. Now, many of those works are on display in a glorious, tightly packed exhibition, “Jackson Pollock: The Early Years (1934-1947),” at the Picasso Museum in Paris.

This eye-opening gem of a show is devoted to Pollock’s lesser-known works. Amid rooms exploring artistic currents important to the American painter, a few Picassos are also hung alongside Pollock’s pieces. But to best appreciate these similarities, it’s important to also take a walk through the rest of the museum’s galleries. With that in mind, we asked co-curator Orane Stalpers, a curator at the museum who organized the show along with curator Joanne Snrech, to help connect the dots between both artists via a few specific examples.

Here is an edited version of her comments.

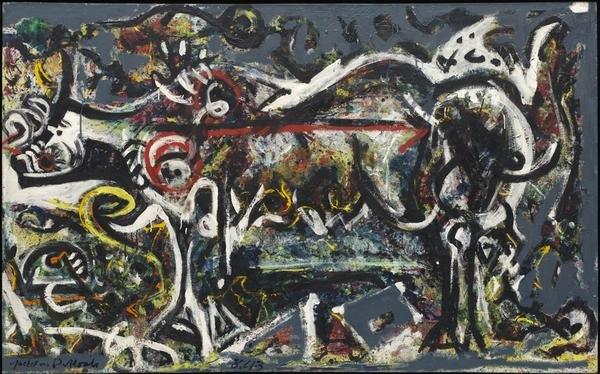

Jackson Pollock Untitled (1938-1941). © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / ADAGP, Paris 2024.

Pollock was very sensitive to the work of Picasso, particularly at the end of the 1930s and beginning of the 1940s, after having seen Picasso’s Guernica [1937], along with a large body of his work and preparatory drawings in a major 1939 MoMA exhibition, and just prior to that, a show at New York’s Valentine Gallery. Pollock often cited the work of Picasso, and was interested in some of this themes, like figures of the bull and horse seen in Guernica, and elsewhere, these tormented figures confronting each other. In the first room, we have the major theme and motif of bullfighting, which interested Picasso and was a starting point for Guernica.

Pablo Picasso, Guernica (1937) on view at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Photo: Herbert Behrens / Anefo.

In Pollock’s work, we can see how he deconstructed figures and used geometrical lines to evoke these forms from Picasso’s oeuvre, which are becoming a bit abstract, in a way. In Pollock’s painting Head [1938-1941], depicting a bull-like creature, you also see how Pollock used the whole canvas, in this very tormented way of painting, and with large brush strokes. [An alternative painting evocative of a bull is shown here, due to limitations on images the museum could make available.] It’s this parallel that we would like to show in this exhibition, as it was a turning point for Pollock in this period. Alongside it is a 1934 Picasso work in black ink depicting a woman holding a candle and, beside her, a horse and bull engaged in battle.

Pablo Picasso, Etude pour Guernica (Tête de cheval) (1937). Courtesy Musée de la Reine Sofia. Photo © Musée de la Reine Sofia, Madrid. © Succession Picasso.

Another room explores Pollock’s psychoanalytical drawings, made beginning in 1941, while he underwent therapy with the Jungian analyst Joseph Henderson to help treat his alcohol addiction. These are not automatic drawings, but they show what influenced Pollock at the time, and Picasso is very present. There is this recurring motif of the tongue drawn like a sharp weapon, that you see in Guernica, which Pollock often cited. In almost all of these drawings, you see Guernica in some way, as well as Native American arts, and biomorphic, more abstract figures that come from Picasso’s Surrealist period in the 1930s.

Jackson Pollock, The She-Wolf (1943). © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / ADAGP, Paris 2024.

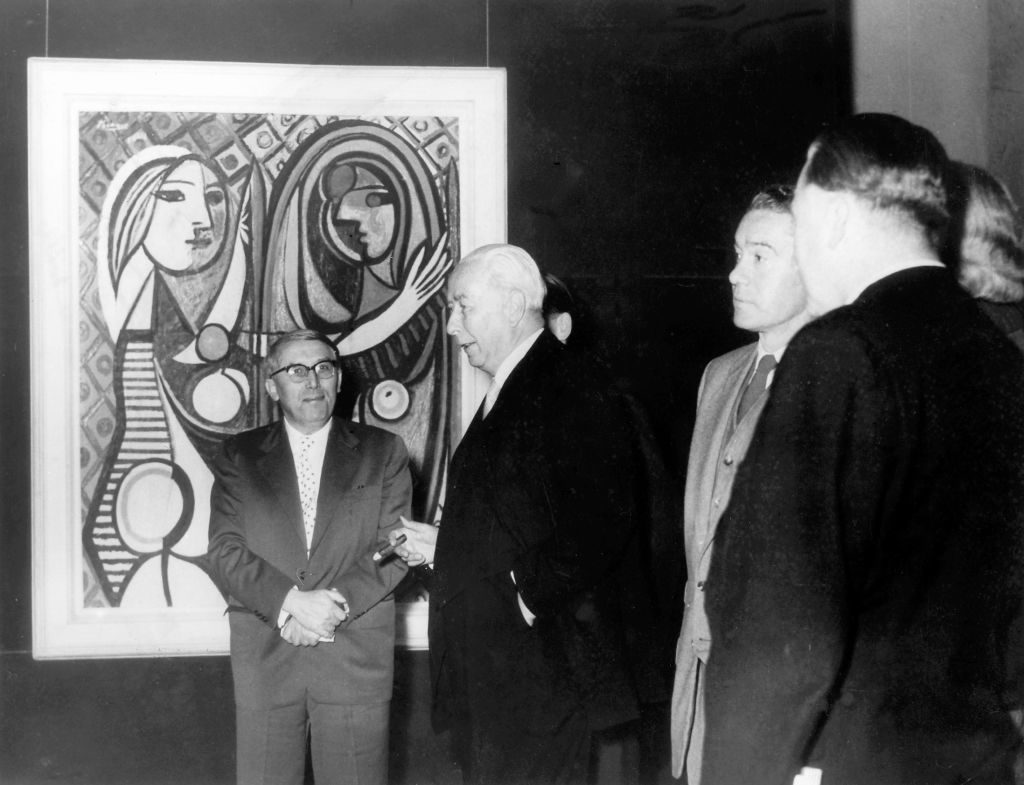

In the 1939 MoMA show “Picasso: Forty Years of His Art,” there was a piece called Woman at the Mirror [1932], which shows the opposition of two figures—probably Picasso’s mistress, Marie-Thérèse Walter. A woman sees herself in the mirror, and you get this sense of opposition between them that can be read in a psychoanalytical way.

German President Theodor Heuss (second from left) talking with the painter Arnold Bode (left) in front of a painting by Picasso during the first documenta in 1955. Photo: picture alliance via Getty Images.

Pollock was really influenced by psychoanalytical studies at the time, and his painting Male and Female [1942-1943] reflects this. The figures in Pollock’s painting—parallel female and male figures—face each other, with a similar composition to that of Picasso’s piece. Jungian theory, which strongly interested Pollock, also emphasizes an opposition between feminine and masculine aspects within each individual. It should be noted that the American painter’s introduction to psychoanalysis came in part from the Surrealists, but also from American intellectuals. Lastly, in this Pollock painting, you also see the influence of Cubism and the introduction of letters in his work. It is really a reflection and an interrogation of Picasso’s work on the part of Pollock.

Jackson Pollock Male and Female (1942-1943). © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / ADAGP, Paris 2024.

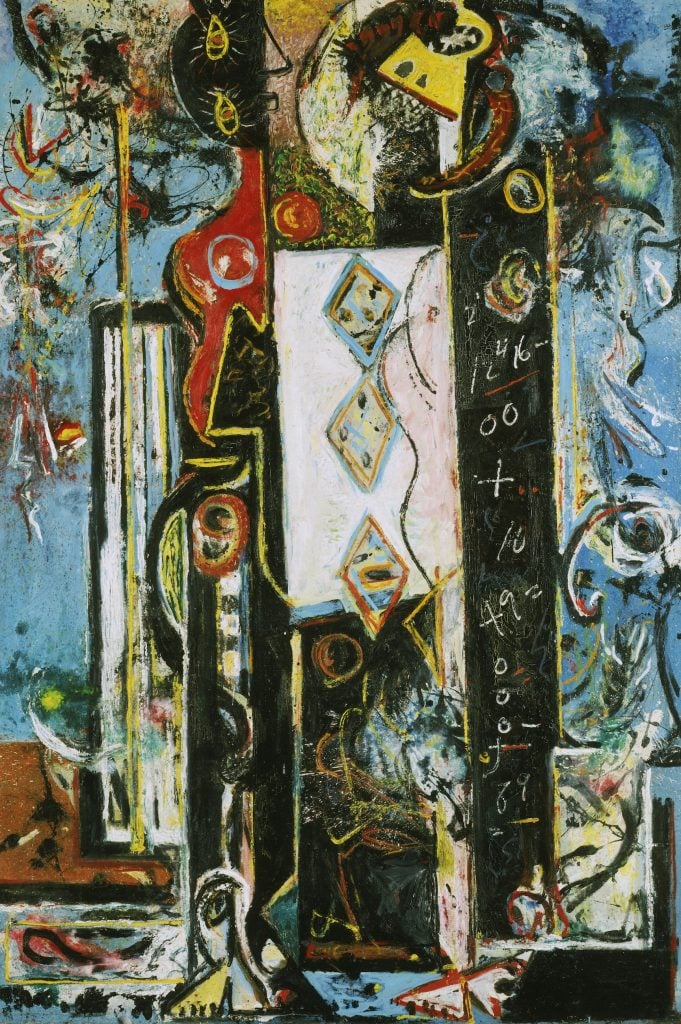

Pollock’s painting The Key [1946] is part of his Accabonac Creek series. It’s an important transitional work for Pollock, because you have this monumentality, and the idea of exploring the frame of the work, almost like an all-over painting. And you have influences from the European avant-garde, including Picasso and, once again, Guernica, which remains present in his work.

Jackson Pollock, The Key (1946). © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / ADAGP, Paris 2024.

In fact, motifs from Guernica are visible here, but reversed and liberally reinterpreted. There’s a woman holding a candle, as well as a tormented bull, or a figure lying on the ground. Pollock also used a more vivid palette than Guernica in these later, though still early works, and importantly, he painted this on the floor. You can see the imprint of the wooden floorboards showing through, which eventually led to the famous drippings.

“Jackson Pollock: The Early Years (1934-1947)” is on view at the Picasso Museum, 5 Rue de Thorigny, 75003 Paris, Oct. 15 to Jan. 19, 2025.