(Image credit: Private Collection)

As a string of new Banksy artworks spring up around London, an expert reveals the clues that unlock his art historical genius.

I

Is Banksy a great artist? When a series of stencilled animals, suspended in silhouette, suddenly began to appear across London in early August, one a day for a week and a half, a chorus of headlines the world over asked: what do they mean?

Warning: This article contains language that some may find offensive.

Was the surprise rash of paintings from Kew Bridge to Peckham – a spree that featured a goat, two elephants, three monkeys, a wolf, two pelicans, a cat, a tank of piranhas, a rhino, and a gorilla helping a gang of beasts break out of London Zoo – nothing more than a static stampede of frivolous fun let loose in the dog days of summer? Or does the sequence contain hints of a deeper message and, just possibly, a clue to what Banksy has been up to all these years?

Having studied every inch of the street artist’s back catalogue for my new book, How Banksy Saved Art History, which explores how his work rewrites the story of art from prehistoric cave paintings to Pop Art, I was intrigued to see where this fresh trail of spray paint might lead us. What I found is that, as ever with Banksy, there is more than meets the eye. Take the City of London police box, the target on Sunday 11 August of the seventh instalment in this series. Banksy’s intervention into the urban object wasn’t nearly as playful as it seemed. Far from simply showcasing a “school of swimming fish”, as initially reported, the circling creatures formed a ghostly shoal of ghoulish piranhas waiting to strike.

Banksy, Piranhas, 2024 (Credit: Getty Images)

By submerging users of the police box in a menacing tank filled with ferocious fangs, Banksy not only echoed the famous formaldehyde-soaked shark by fellow British artist, Damien Hirst (with whom he has collaborated in the past), but took Hirst’s work to the next level of meaning. Thirty-three years since Hirst first unveiled his vicious vitrine, that once-shocking shark has begun to lose its bite. By updating the YBA icon and resharpening its resonance in the context of policing, Banksy rehabilitates a work whose relevance was a little long in the tooth.

Damien Hirst, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, 1991 (Credit: Getty Images)

This is what Banksy does best and what elevates his work above perishable pranks: he re-inflects fatigued masterpieces with a pertinence we have ceased to believe they could have. Far from defacing or demeaning the artists into whose works he regularly intrudes, from Leonardo to Basquiat, Banksy invites us to look again at what makes them great. What follows is a selection from my new book of some of the most powerful examples of how Banksy has duffed up art history, shoved it against a wall in the dead of night, and, in doing so, reinvigorated it.

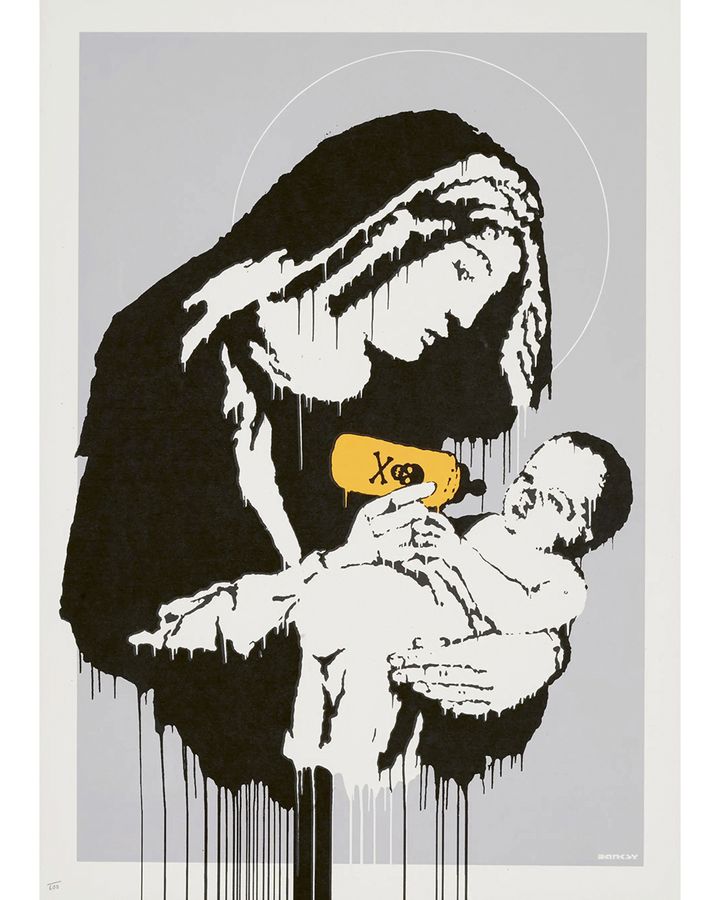

Elisabetta Sirani, Nursing Madonna, 1663 / Banksy, Toxic Mary, 2003

Banksy, Toxic Mary, 2003 (Credit: Private Collection)

Elisabetta Sirani, Nursing Madonna, 1663 (Credit: National Gallery, Prague)

At first glance, Banksy’s disquieting 2003 print Toxic Mary, which imagines the infant Christ feeding from a bottle of poison, may seem merely a meme of its moment. It appeared to echo the anti-religious sentiments of prominent proponents of what came to be known as the New Atheism, including Richard Dawkins, Christopher Hitchens, Sam Harris, and Daniel Dennett, who insisted that religion is a pernicious force. But is that really what the image says? Look closer and Christ is, after all, a helpless victim. Recalling Old Master portrayals of the Virgin Mary nursing her son – a tradition that extended from the late Middle Age to the 17th Century and was known variously as Virgo Lactans (The Lactating Virgin) or Madonna del Latte (My Lady of Milk) – Banksy taps into a vein of theological thought that seeks to trace the source of Christ’s spiritual authority. The shocking image reminds us that conventional portrayals of the Mother and Child are anything but simple or straightforward depictions of pure maternal love. They are audacious maps of perilous power.

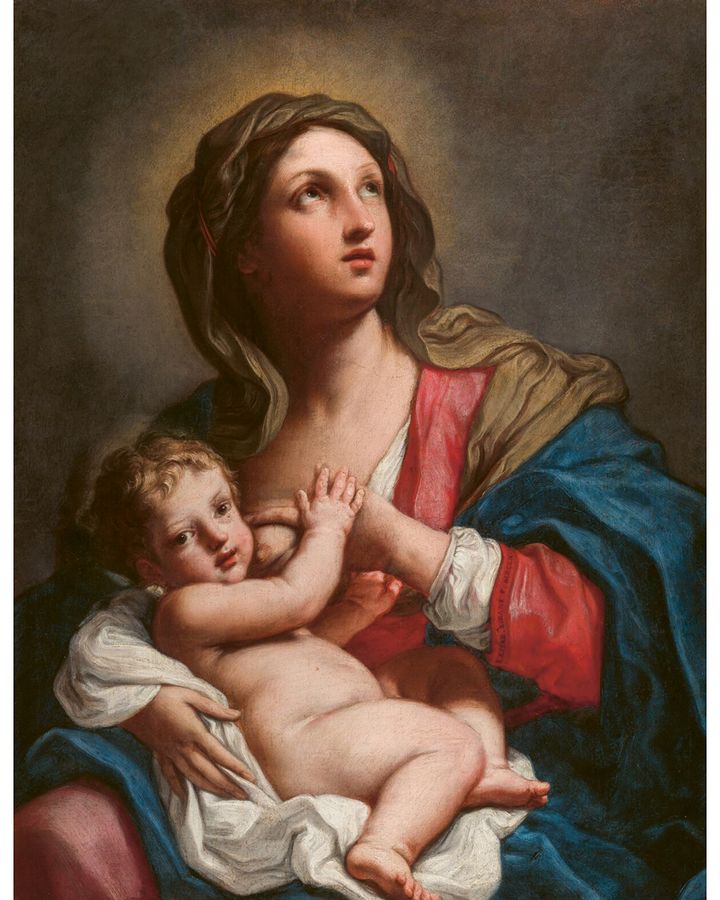

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait at the Age of 63, 1669 / Banksy, Rembrandt, 2009

Banksy, Rembrandt, 2009 (Credit: Private Collection)

Rembrandt, Self-Portrait at the Age of 63, 1669 (Credit: National Gallery, London)

Rembrandt saw seeing differently. In 2010, a team of researchers at the University of British Columbia proved it. Using computer-rendering software, they demonstrated how our gaze, when directed towards a Rembrandt self-portrait, is subliminally lured into the Dutch master’s own meticulously depicted eyes before being “guided” through a sequence of cues and clues that bounce our pupils around the canvas like carefully controlled pinballs. As if anticipating the study, Banksy a year earlier, in 2009, likewise drew attention to Rembrandt’s eyes with his deceptively silly send-up of the Dutch artist’s Self-Portrait at the Age of 63 (1669), on to which he affixed a pair of joke googly eyes. By the time Banksy revealed his facetious rendition of Rembrandt’s likeness, the whole world had found itself wearing Google goggles when it came to seeing, well, everything. “If it isn’t on Google”, as the founder of Wikipedia put it, “it doesn’t exist”. Fixated on the small screens of our smartphones, society’s seeing has altered irrevocably. If Rembrandt’s celebrated portraits are emblematic of an era that sought to see deeper and further, Banksy’s slapstick riff offers a fitting portrait of our own boggle-eyed, image-addled age.

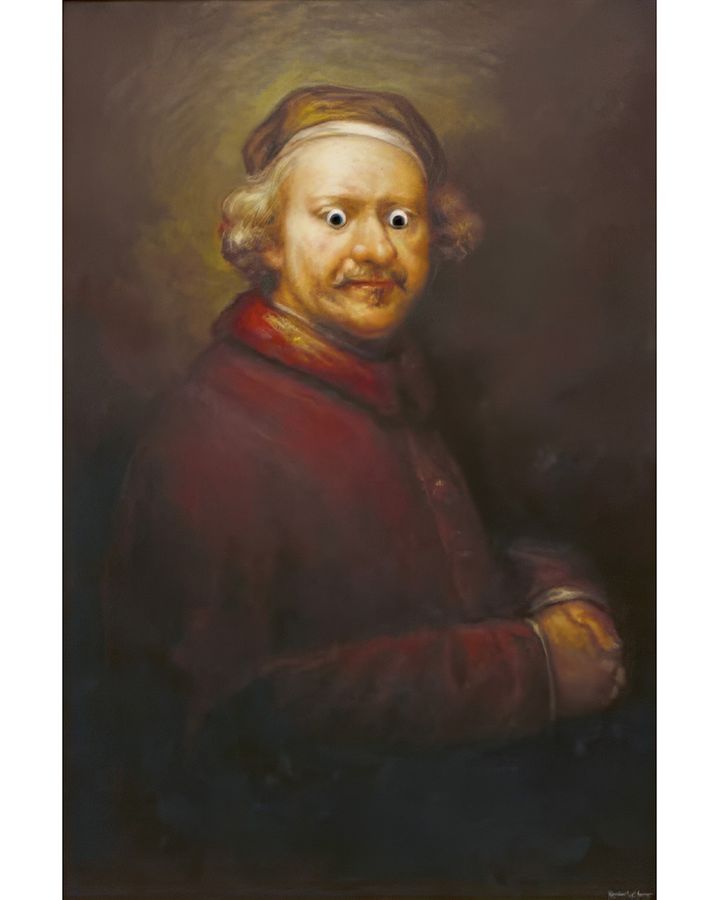

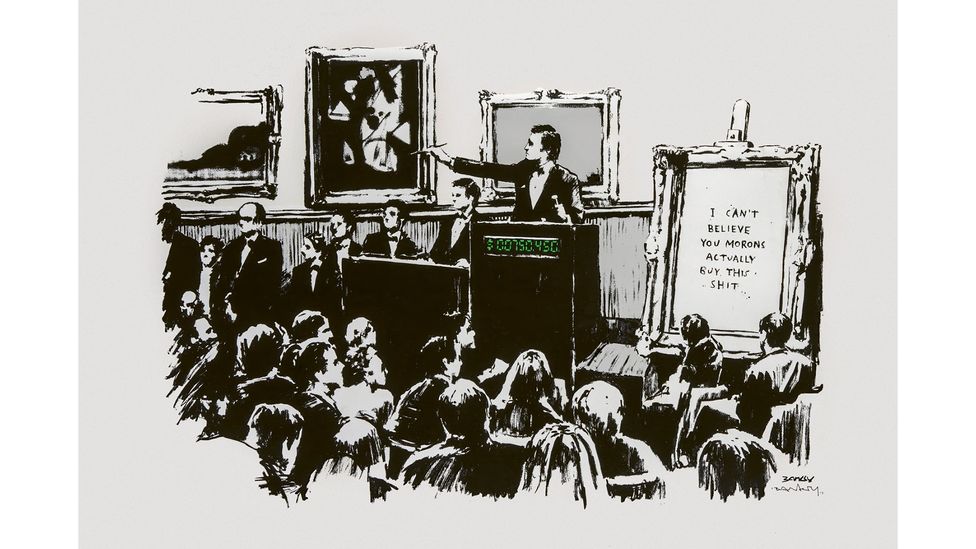

Thomas Rowlandson, James Christie on the Rostrum at Christie’s Auction Room, 1801 / Banksy, Morons, 2007

Banksy, Morons, 2007 (Credit: Private Collection)

Thomas Rowlandson, James Christie on the Rostrum at Christie’s Auction Room, 1801 (Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1917)

There is a long tradition of artists despising the very art world they inhabit. Take British caricaturist Thomas Rowlandson’s 1801 watercolour James Christie on the Rostrum at Christie’s Auction Room, which questions the moral integrity of those attending an art auction. There is something insalubriously sweaty about the crush of lecherous old men leering at the reclining nude on the auction block as they size up younger girls in the crowded gallery. It’s an orgy of ogling. Did Banksy have Rowlandson’s watercolour in mind when, in 2007, he created his own unmerciful print Morons, which showcases a scrum of pretentious art collectors desperately bidding for a work whose unmistakable message mocks their very existence: “I can’t believe you morons actually buy this shit”? Who knows. What is clear is Banksy’s unreserved disdain for an elitist scene that has witnessed his own work elevated and feverishly fought over – in spite of its hasty execution and anti-establishment meaning – hasn’t harmed his reputation in the slightest.

John Constable, The Hay Wain, 1821 / Banksy, Crude Oil Jerry, 2003

Banksy, Crude Oil Jerry, 2003 (Credit: Private Collection)

John Constable, The Hay Wain, 1821 (Credit: National Gallery, London)

In his 2003 painting Crude Oil Jerry, which summons the dappled splendour of the widely-adored English Romantic painting The Hay Wain, then sets it alight, Banksy appears to reveal the “con” in Constable. The iconic idyll by the British landscape artist John Constable, which seems at first glance to celebrate unspoilt countrysides, streams rippling with pristine water, and innocent sunshine so soft it wouldn’t dream of damaging your skin, is of course a bunch of halcyon hooey. Even Constable, who created the work in the shuttered solitude of his studio, recalling the scene from his childhood, knew what he was depicting had already disappeared into the thickening smog of accelerating industrialisation. By superimposing – on to the pastiche pastoral of a recycled canvas – the figure of the indomitable mouse from the cartoon duo Tom and Jerry, perched upon a leafy limb, holding a can dripping with flammable fuel in one hand and a lit match in the other, Banksy asks us to look again at what Constable has really portrayed – a tired and tinder-dry lie to which we’ve long ago put a match we can’t unstrike.

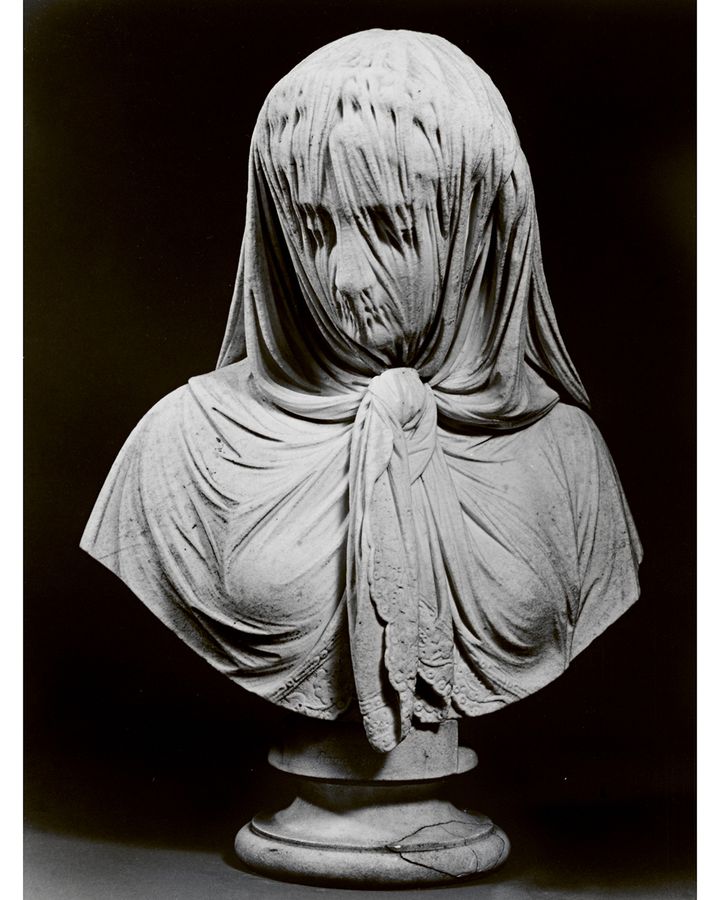

Giovani Battista Lombardi, Veiled Woman, 1869 / Banksy, Bataclan Theatre Paris, 2018

Banksy, Bataclan Theatre Paris, 2018 (Credit: Photo Lucile Gourdon/Sipa/Shutterstock)

Giovani Battista Lombardi, Veiled Woman, 1869 (Credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gift of Robert L Isaacson, 1984)

The bust of a veiled woman created by the 19th-Century Italian sculptor Giovanni Battista Lombardi in 1869 is a miracle of poignant craftsmanship. The young woman it portrays, frozen forever in mourning, is seen with a veil pulled tight across her sorrowful face – its fragile folds and delicate pleats preserving a semblance of her youth while offering a prescient glimpse of her complexion’s slow shrivel into old age. The bust’s ability to hold in equilibrium an innocence that is slipping away and a maturity that may never be reached makes it a fitting source for one of Banksy’s most moving murals. Stencilled on to the exit door of Paris’s Bataclan theatre in the summer of 2018, two-and-a-half years after that venue was the site of a terrorist attack in which 90 concert-goers were murdered by Islamic extremists, Banksy’s mural fits Lombardi’s touching portrait with a protective suit of a security service responder. She stands solemn sentry by the door through which many in the crowd of 1,500 tried desperately to escape, haunting the portal like a soul summoned from another world.

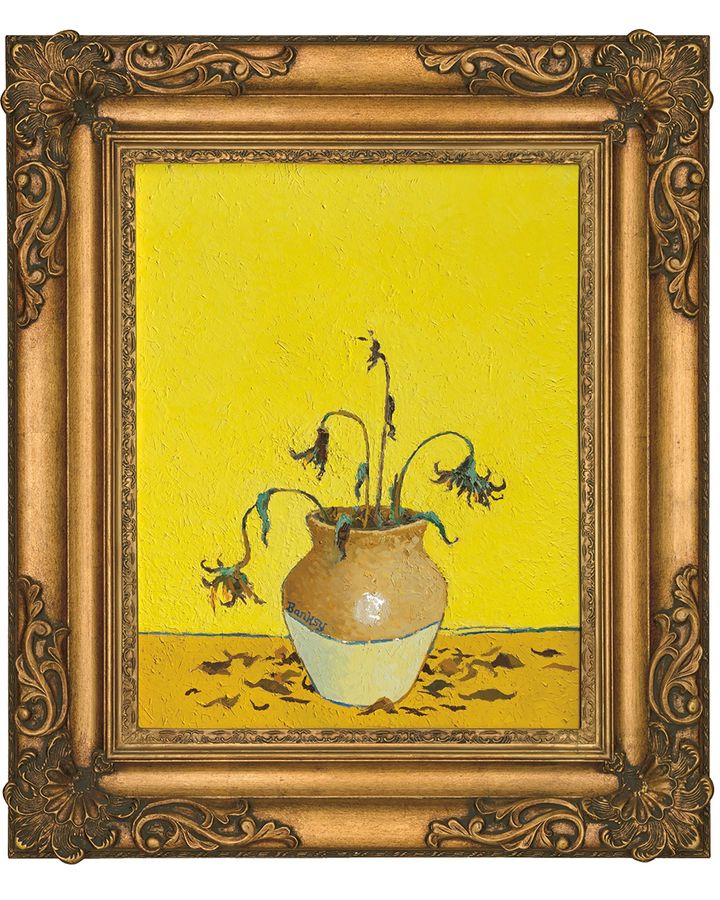

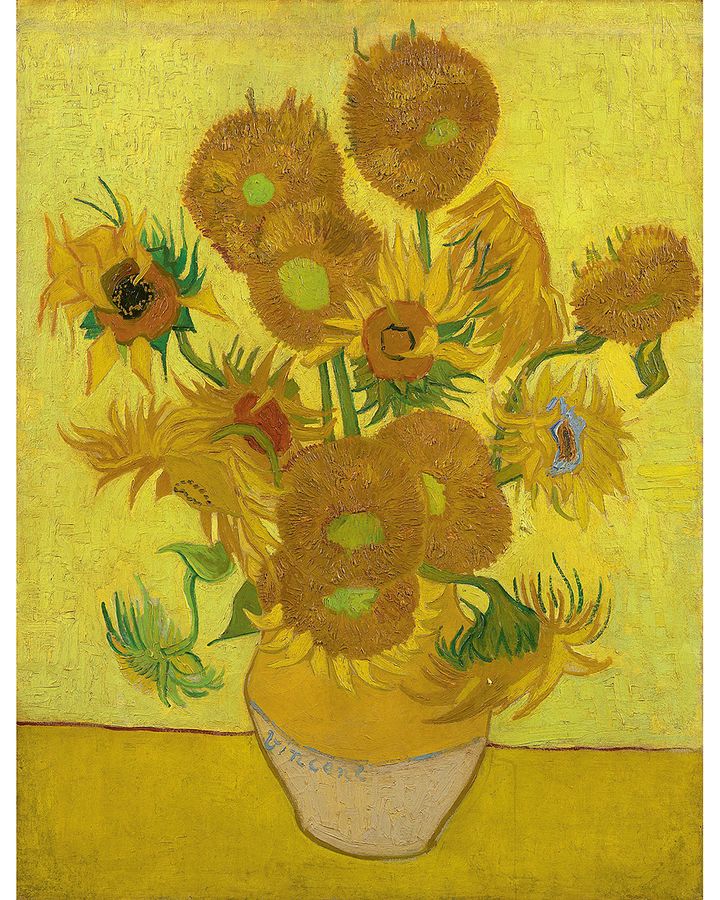

Vincent van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1888 / Banksy, Sunflowers from Petrol Station, 2005

Banksy, Sunflowers from Petrol Station, 2005 (Credit: Private Collection)

Vincent van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1888 (Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation))

Banksy has a knack for fracking into deep reserves of latent meaning. Consider his 2005 take on Vincent van Gogh’s revered still life Sunflowers, 1888, which the street artist rechristened Sunflowers from Petrol Station. Van Gogh’s original canvas was begun in eager anticipation of the arrival of his friend and fellow artist, Paul Gauguin, with whom he was planning to share a rented house in Arles, in the south of France – a visit that would turn south when Van Gogh turned a knife on his friend before using a razor to slice off a portion of his own left ear. As if seizing on the complexity of the painting’s troubled backstory, Banksy strips the bouquet’s now-stooping stems (which he has slimmed from 15 to four), and scatters about the table on which the vase sits a ragged carpet of shrivelled florets, like so many severed lobes. By drolly dislocating Van Gogh’s intensely intimate canvas to the seemingly out-of-the-way context of “petrol stations” and “crude oil”, Banksy challenges us to consider to what extent meaning in art, like fossil fuels in earth, is a finite resource that we can only exploit for so long. At some point, the vessel is empty. And so are we.

Claude Monet, Japanese Footbridge, 1899 / Banksy, Show Me the Monet, 2004

Banksy, Show Me the Monet, 2004 (Credit: Private Collection)

Claude Monet, Japanese Footbridge, 1899 (Credit: National Gallery of Art, Washington DC)

In May 2004, one of Claude Monet’s many depictions of a pond in the French Impressionist’s garden in Giverny captured headlines when it sold for $17 million at auction, an eye-popping price tag that seemed at odds with the pulsing purity of the paradise Monet was presenting. A year later, Banksy responded, as only Banksy could, with his painting Show Me the Monet. Banksy’s satirical oil-on-canvas conflates three different instalments of Monet’s water-lily series and imagines the artist’s famous Japanese footbridge embattled by the jutting fossils of urban dishevelment – discarded traffic cones and the steel skeletons of stolen shopping trolleys. Far from polluting the surface of Monet’s canvas, however, Banksy’s interventions accentuate aspects of the work that have been rusting under its surface for a century. The abandoned traffic cones call to mind Monet’s uncurbed taste in expensive automobiles, which he had his chauffeur race through village streets (a habit that earned him a traffic violation). As for the trolley, Monet was an equally incorrigible shopper. Many of the lilies we see shimmering on the glassy surface of his work were brought in from Egypt and South America – an invasive practice local authorities demanded Monet stop for fear that it might place local aquatics at risk. The artist refused. Banksy’s Show Me the Monet doesn’t deface the underlying masterpiece. It lays it bare.

How Banksy Saved Art History by Kelly Grovier is published on 12 September by Thames & Hudson.

—

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can’t-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.

For more Culture stories from the BBC, follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram.

;