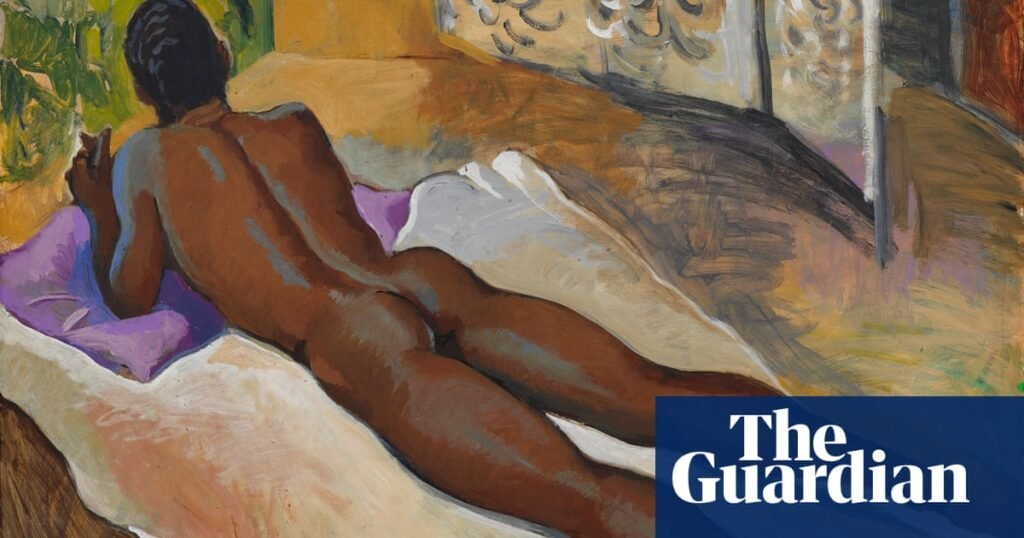

The first time I ever saw a black male nude was in a Boscoe Holder painting in a private collection in Trinidad. It was beautiful – and so brazen that I wondered whether it broke the country’s lingering Victorian-era indecency laws. I would later discover he had painted hundreds more, many for his eyes only, never intended to be shown in his lifetime.

From Saturday at Victoria Miro in London, many will be shown in a joint exhibition with his younger brother Geoffrey, whose similarly radiant, sensual paintings of black men and women reflect just how far ahead of their time the Holder brothers were. Born in Port of Spain, Boscoe in 1921 and Geoffrey in1930, to an inspired middle-class mother from Martinique and an upwardly mobile Bajan father, the siblings were nurtured in a milieu of what art historian Erica James calls “an incredible generation of Caribbean people”.

The brothers were schoolmates with Nobel prize-winning author VS Naipaul and grand master of Trinidadian art Carlisle Chang, with whom Boscoe later joined the iconoclastic movement known as the Independents. Boscoe was a prodigious piano virtuoso from a young age, learning to play by ear, and he was hired to perform at functions in the grand houses, where he saw art on the walls and in books.

“Music informed his life and work, from his BBC TV show Bal Creole to introducing steel pan to this country and Afro music to a wider public,” says British artist Peter Doig, who bought Boscoe’s extensive record collection after his death in 2007, and more than 100 of his erotically charged male nudes – some full frontal, many still unseen.

The polymath siblings would go on to become Trinidad’s most wildly prolific, genre-hopping artists of the 20th century. Though both spent decades away from the island – in London and New York, touring Europe and Latin America as dancers, musicians, choreographers, socialites, and in Geoffrey’s case a Hollywood actor – the vital pulse and colour of urban Trinidad shaped their creative spirits.

“They were decades ahead of Black Lives Matter and gay rights,” says Trinidadian artist Eddie Bowen, whose encounters with Boscoe – who had returned home from London in 1970 after two decades in which he performed on TV, in cabaret nightclubs and at the Queen’s coronation – were characterised by Boscoe’s outrageous sense of humour, impropriety and cutting remarks. “Boscoe claimed the oeuvre of representing the black body, but in his day it wasn’t such a political statement, it was an aesthetic and social statement.”

Christopher Cozier, Trinidad’s most successful contemporary artist, sees the Négritude philosophy of the 1940s Harlem Renaissance in Boscoe’s work, a different expression of blackness to that which Cozier witnessed in the Trinidadian Black power movement of the 60s and 70s. “It’s a site of exchange around blackness and how blackness has to articulate itself through style and body language. There’s a dualistic side to Boscoe. If you talked to him long enough, he’d say horribly indiscreet things in a dandy-esque way.” Cozier laughs. “That side of things is only hinted at if you look deeply into the paintings. On one side, there’s utopianism, black Creole glamour, well-dressed people cutting a figure. On the other, there’s cynicism and aggression.”

Perhaps Holder’s dualism came from being black in a British colony where the US established a second world war base, where being gay was frowned on, and where Trinidad’s blend of African, Indian, European, Chinese, Middle Eastern, Latino and Indigenous people provided a heady cultural mix. Late in his adolescence, he had a nervous breakdown.

“Colonial life wasn’t easy,” says his son Christian, who has edited a collection of essays about his father. “He was a teenager supposed to be playing cricket, but he was drawing nudes in the back of his textbook. He had aspirations bigger than the island. He knew there was more waiting.”

Trips to Martinique and New York in the late 1940s were “life-changing”, Christian says, teaching Boscoe about the clothes he dressed his models and dancers in – one of whom was his wife, dance partner and muse, Sheila Clarke – and the choreography he had learned as a collaborator turned rival of Beryl McBurnie. His 20 years in London with Clarke were a riot of frenetic entertainment. Christian recalls how “austere postwar Britain with its ration cards and children playing on bomb sites” lapped up his newly arrived bohemian parents, “with their feathers, frills, shak-shaks and penny whistles”.

Geoffrey’s path mirrored his older brother’s, though his was “version 2.0”, his son Leo says. “Boscoe was there first. Nine years makes a big difference when one is mentor and one mentee. Geoffrey was born into a different world and family. The younger one will usually be more elastic in his worldview, and Geoffrey’s fluidity transfers to his paintings.”

James curated a solo show of Geoffrey’s work in LA in February where fluid lines and seductive textures were abundant – as they are at Victoria Miro. Seeing them divided into two exhibitions with each brother’s work in different rooms, audiences might get the impression that Geoffrey was more sophisticated and futuristic, which isn’t the case. The curation of Boscoe’s work focuses heavily on nudes, ignoring his portraits, much cherished in Trinidad where he was a society painter, and his landscapes, which rank alongside those of Trinidadian greats such as Michel-Jean Cazabon, Amy Leong Pang, Sybil Atteck, Knolly Greenidge and Jackie Hinkson.

“Geoffrey was fascinated by what Boscoe could do, and imitated him,” says James. “If Boscoe danced, he would dance. If Boscoe painted, he would paint. Their synergies propelled them,” she says.

Geoffrey made his stage debut at seven when Boscoe stowed him away in a box of costumes, unbeknown to their parents, taking him to McBurnie’s Little Carib Theatre in nearby Woodbrook. In the foreword to Geoffrey MacLean’s 1994 Boscoe Holder biography, Geoffrey describes growing up with his brother as “like living under the wing of the Wizard of Oz … I listened to Boscoe play Chopin’s Nocturnes in the morning, became intoxicated inhaling turpentine and linseed oil from his oil paint in the afternoon, and followed his footsteps in the evening when he rehearsed with the dance company. My world was enchanted. I had no need for fairytales.”

In the 1950s Geoffrey moved to New York where he married LA-born dancer Carmen de Lavallade, danced in the Metropolitan Ballet and starred in Truman Capote’s Broadway musical House of Flowers as a character based on Haitian Vodou deity Baron Samedi. In 1973, he revived the role as a Bond villain in the Roger Moore classic Live And Let Die.

In the early 1980s, Cozier spotted Geoffrey from the window of an apartment in Soho. “I would see people like Robert De Niro in their tracksuits and one morning I saw Geoffrey in a white suit, hat and walking stick. By then, he was a celebrity because of his 7-Up advert. The act of buying oranges had such grace and style it was like watching a performance.”

after newsletter promotion

A 1982 Boscoe portrait titled Two Cherubs captures Cozier and his artist wife, Irénée Shaw, after a chance meeting in the Belmont neighbourhood where Boscoe’s studio was – it captures his sensuous style, somewhere between impressionist and modernist. “At his very best, Boscoe gets close to Degas,” says Doig, describing a “consummate and compulsive” painter who, on visiting someone’s house would immediately empty his bag of brushes and start painting. Relaxing with friends, he might sketch them impromptu, just like Geoffrey would draw “anywhere, on a jet, in a limousine”, says Leo. “He didn’t spend one day of his life not creating.”

While Geoffrey painted mostly from memory, Boscoe’s subjects sat for him – ordinary people and icons alike, including the calypsonian singer Mighty Sparrow. Boscoe went back to Trinidad partly because in Europe’s museums he didn’t see any of his own people – people such as Kathleen Rollock, the model Boscoe painted more frequently than anyone from the day she met him on Frederick Street aged 13.

“He was acting like he’d won the Lotto and asked if I knew who he was,” says Rollock. “I’m half black and half Indian. Boscoe loved his heritage, loved women, and I embodied every Trinidadian woman.”

“There are paintings of his gardener who had an incredible cat-like face with big eyes,” Doig says. “I was told a funny story that Sheila was looking for the gardener to clean out the gutter and couldn’t find him, so she goes to the studio and there he is lying on the chaise longue, Boscoe painting him.” Some claimed to have posed for Boscoe with their underwear on, only to find themselves naked in the finished painting.

Writer Attillah Springer provides the accompanying text to the show and says the Holders “grew up in a time without access to portraits of black people, but Trinidad was producing frontline pan-Africanists. To represent blackness as beautiful was the most radical action they could have engaged in.”

Doig spent his childhood in Trinidad and returned there to live and work in 2002 with his friend Chris Ofili, who also owns some Boscoe works. He co-curated a Boscoe show in Berlin in 2010. After Boscoe died, Doig and his family lived in the house in Port of Spain that Boscoe had made into his studio. “A magical place,” he reflects. Doig’s painting of his teenage daughter in a hammock, Alice at Boscoe’s, was painted in the dense tropical garden and shown at his last major exhibition at the Courtauld Institute in London.

He recalls his acerbic introduction to Boscoe, who came to the front door of that same house, now an art gallery, to receive a bag of oranges as a gift. He told Doig he once had a tree that never bore fruit. “A friend told him that if you piss on a tree’s roots it helps the fruit grow, to which Boscoe just muttered: ‘There’s plenty of people around here who could drink my piss, I wouldn’t waste it on a tree.’ I thought that was absolutely hilarious, just seconds after meeting him.”

On Geoffrey’s death in 2014, he left a personal archive of thousands of books, photographs, costumes and ephemera. Leo has spent years archiving it and has donated much of it to the Emory University in Atlanta and the Institute of Black Imagination. Boscoe’s library, containing books on Finnish homoerotic artist Tom of Finland and portraitist Don Bachardy, partner of Christopher Isherwood, was sold at a fabled house sale after his death.

“They had a lot of interest in other artists,” says Doig. “They weren’t just in their own world.”

Their own world, however, as their paintings show, was an irresistible, alluring place.