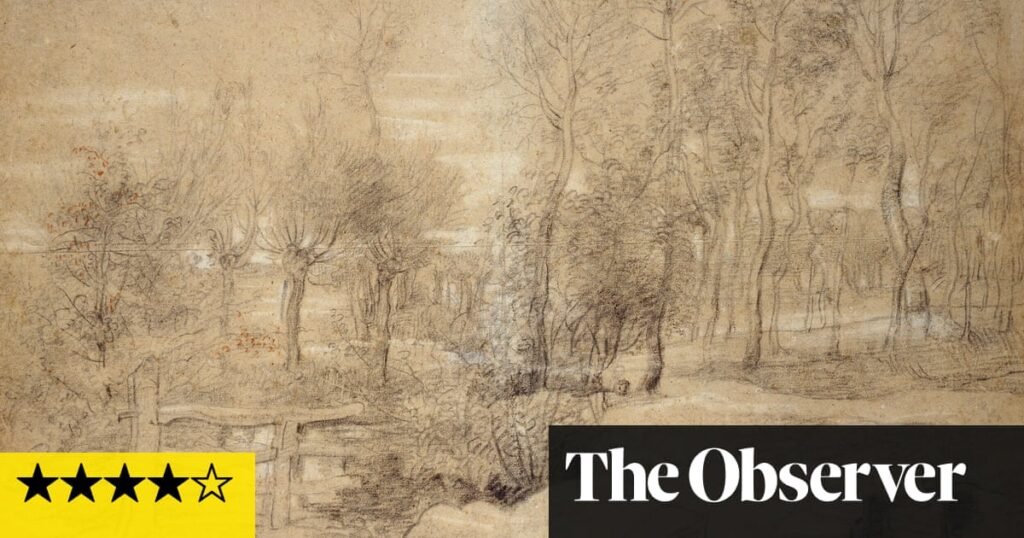

Mist descends at dusk along the path through a forest. Pale water, motionless beneath a footbridge, holds the last of the light. Pollarded willows raise their amputated arms, as if in warning, while slender elms lead invitingly into the distance. It is a scene of ominous enchantment – should you stay or should you go?

Peter Paul Rubens, flushed with a lifetime’s success, has bought a country manor outside Brussels. He takes a sheet of oatmeal paper out into the grounds with a stick of charcoal. The drawing, made purely for his own purposes, one feels, is so mysteriously beautiful it stops visitors in their tracks at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford: Rubens in private, his fascination with the landscape now become ours. It is a crossroads all of its own in this enthralling show.

Bruegel to Rubens is the very best of the best Flemish drawings through roughly a century. When the Belgian government published a list of the nation’s greatest graphic masterpieces in 2020, 100 were displayed at Antwerp’s Plantin-Moretus Museum, home of the world’s oldest printing presses. More than half are now united here with the Ashmolean’s own spectacular images for a precious few weeks in the light. By late June, these fragile visions must all return to the protective darkness from which they came.

They are vital, intimate, exceptionally intense. You are looking directly at the mind and hand of these artists at work. Here’s an earthworm straight from the garden, observed as it slowly glides at full length in all its blue and pink iridescence: a portrait of a 16th-century invertebrate. Here’s Johannes Fijt’s harum-scarum dog, bristling across a page of tinted watercolour as if in pursuit of a disappearing cat.

Jacob Jordaens looks out of his Antwerp window in the autumn of 1659 and sketches five women arguing about the latest politics in the marketplace. Mark my words, says one woman, holding up a wagging finger; I am not so sure, ponders the young lady on the verge of the group. This is what I saw, writes Jordaens, on the morning of 1 October.

The show reaches all the way back to Pieter Bruegel’s 1554 sepia ink landscape of hazy summer trees, a cow turning its head placidly in our direction as if interrupted chewing the cud; and all the way forward to Justus van Egmont’s group of figures strolling through a park circa 1660, all got up in Paris fashions like some future fete galante by Watteau.

A startling self-portrait from the same era, by Jan Cossiers, shows the artist snub-nosed, wide-eyed and slightly dazed at the effort of leaning back to catch himself in the mirror, mouth effortfully open. His hair cascades in loose locks way down his chest, washed in with grey watercolour over black and red chalk.

This is an astonishing era for invention. You see it everywhere through the show. It is in Joris Hoefnagel’s multicoloured shells, birds and butterflies, so beautifully arranged on the page like gifts on a tray, and indeed made for the friendship books passed back and forth between Flemish artists and intellectuals. And in Paul de Vos’s glorious table of fruit, so light and witty in its penmanship, it resembles an Edward Ardizzone. A quickfire squirrel steals a nut from the top of the pile.

Vos adds sepia and cerulean to turn his drawing into a delicate watercolour. With just a touch of cobalt to an eye or rosy pink to a cheek, colour transforms a Flemish sketch into a saleable painting. A finger dabbed here and there to smooth the colour is visible even now, along with the live sense of nib and quill and fugitive pastel.

And living history runs through the art. Maerten de Vos has the job of decorating the walls of Antwerp for the official visit of Archduke Ernest of Austria in 1594. His wild design for Cadmus and Hermione – a castle sprouting from her head, dragon wings from his body, exactly according to Ovid’s Metamorphoses – will appear above an arch, before weather washes it away.

And later, in the same streets, an artist sketches William Cavendish, Duke of Newcastle, who has fled England after the civil war. He is still got up in swagger boots and silk, but carrying a whip, having just bought Rubens’s old house to turn it into a riding school.

Antwerp is the source of so much flair and innovation partly because of the etcher Hieronymus Cock and Christophe Plantin of the printing press. Cock made prints from Pieter Bruegel’s drawings, supreme among them the irreducibly weird scene in this show. The temptations of St Anthony emerge – fittingly – out of a giant head, tongue lolling, men emptying pots from the mouth, a heron pecking hungrily at one eye. Birds fly up from a landscape filled with anarchic imaginings, all arriving at the speed of thought on the page.

But Rubens is even more central to Flemish drawing; many of these artists passed through his colossal workshop. Star among them is Van Dyck, represented here with a virtuoso hand clasping a pike on one side of the page and a full-scale dying Christ on the other.

With almost two dozen works in the show, Rubens is the constant fascination. You see his mind evolving through time, from his teenage animations of Bruegel’s prints to his early drawings of ancient Roman statues brought alive through the graphic glint of an eye.

His livewire portrait of the Earl of Arundel is all piercing intellect and coruscating line. Eyelash by tendril by whisker by hair, the diplomat seems to be coming into being as you look. But yet more staggering are the stranger images in this show that reveal a deeper Rubens than one ever knew: a mind of shadows and dreams, of lingering moonlight and early dawn, and of ghostly tracks disappearing away into the distance, still quick with the maker’s mark.