There are many things to know about James Barnor: but first and foremost is the fact he is Ghana’s most influential photographer and photojournalist. Secondly, he spent six decades crafting a beautiful body of work that stretches beyond documenting Ghana’s pre- and post-colonial viewpoint to explore the exuberance and liberal enthusiasms of London.

A look into James Barnor’s career

James Barnor surrounded by his band, Fee Hi, during his 95th birthday celebration at the British High Commission, Accra, 6 June 2024

(Image credit: Nii Odzenma)

Now a youthful and agile 95 (born in 1929), Barnor is currently enjoying his retirement at his London home, where he tells me that he’s occupied more than ever, immersing himself in past images. ‘My retirement seems as occupied as before, with so many past images to go through. I lost quite a number of negatives, but there is still a lot now in a database, to be captioned. I need all the time to go through and try to remember when they were taken and where, but most importantly who is in the photos. Honestly, I had hoped to spend my retirement reading books! None of that now,’ he says.

Naa Jacobson as Ballroom Queen after a fashion show, Ever Young Studio, c.1955

(Image credit: James Barnor. Courtesy galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière)

Barnor’s 95th birthday in June 2024 was marked with a month-long festival celebrating his life and legacy back home in Ghana. He returned on a visit that gave him the opportunity to connect with old friends, family and places. He tells me his favourite part was ‘meeting members of my Ebaahi Gbiko / Feehi Cultural troupe (most of whom I travelled to Italy with in 1983, when they were schoolchildren); [they were] still able to perform the wonderful dances that took them places!’

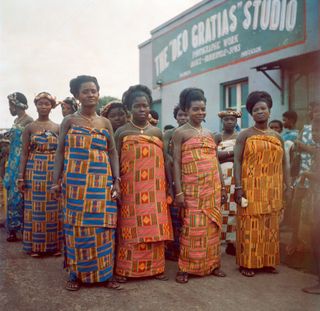

Odwira Otublohum festival, High Street, 1970

(Image credit: James Barnor. Courtesy galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière)

The festival was put together by the team at Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière in Paris, who for seven years have been creating an archive of 40,000 images taken by Barnor during his career. For them, it felt important to celebrate these works while Barnor still lives, and in a place that shaped his practice.

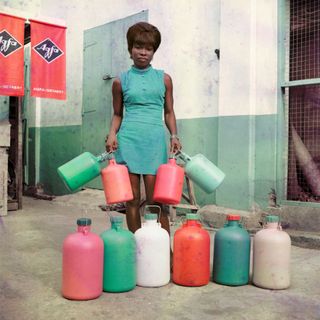

Filling up the Studio X23 car at the Agip petrol station for its 1974 calendar, Accra, 1973

(Image credit: James Barnor. Courtesy galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière)

‘This project brought together a lot of people in Accra and Tamale,’ says the festival’s producer, gallery founder Clémentine de la Féronnière. ‘In Ghana, we had closing talks between a new generation of artists and maybe the next generation.’ Linking to Barnor’s archive, she adds, ‘Rita Mawena did a workshop on how to archive – proposed to anyone who has [images to archive, even] family pictures.’

James Town’s lighthouse, in front of the street where the Ever Young Studio was standing, 1953

(Image credit: James Barnor. Courtesy galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière)

Barnor’s decades-long career is worthy of a long look. It began with his early days in the 1950s, when he worked as a freelance photographer for the Ghanaian media, and founded his Ever Young Studio, where he focused on portrait photography and pretty much documented Ghana’s burgeoning political independence, capturing figures including Kwame Nkrumah, Ghana’s first president.

A traffic officer on duty in the business district (Atta Mills High Street), Accra, 1970s

(Image credit: James Barnor. Courtesy galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière)

Towards the late 1950s, he went to the UK to study at the London College of Printing. It was also around this time he worked with DRUM magazine, documenting urban Black culture with a focus on West and East Africa. In the 1960s, he took the chance to study at the Medway School of Arts in the UK, and by the early 1970s, he had returned to Accra, where he established the city’s first colour photography studio, called Studio X23.

Kwame Nkrumah welcomed home upon his return from London in 1957 after the conference of Prime Ministers of the Commonwealth, Accra, July 1957

(Image credit: James Barnor. Courtesy galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière)

Despite his decades of documenting Black culture across the continent, Barnor’s photography is only now getting the recognition it deserves. His influence continues to shape the work of contemporary artists and photographers, such as Campbell Addy and Tyler Mitchell. ‘It’s impressive to see a lot of young, and not that young, artists and photographers mention Barnor as a major inspiration,’ says de la Féronnière.

Sick Hagemeyer shop assistant posing in front of the United Trading Company headquarters, Accra, 1971

(Image credit: James Barnor. Courtesy galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière)

Further events and exhibitions are expected to run until summer 2025, the majority dedicated to Barnor’s work, while others will include photographers and artists asked to make works that interpret his archive.

Salah Day, Kokomlemle, Accra, 1973

(Image credit: James Barnor. Courtesy galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière)

Sick Hagemeyer shop assistant, c. 1970

(Image credit: James Barnor. Courtesy galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière)

Evelyn Abbew washing prints at the Ever Young Studio, c. 1954–56

(Image credit: James Barnor. Courtesy galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière)