Artists such as Ambika Dhurandhar and Amrita Sher-Gil emerged as rare exceptions in this milieu, recognised for their work during the colonial period and the early years of Indian independence. Dhurandhar was a modernist painter and one of the first women to graduate from the Sir JJ School of Art, Mumbai. She participated in exhibitions and salons, and won a number of awards at competitions organised by art societies across India. She eventually became a Fellow of the Royal Society of Art, London.

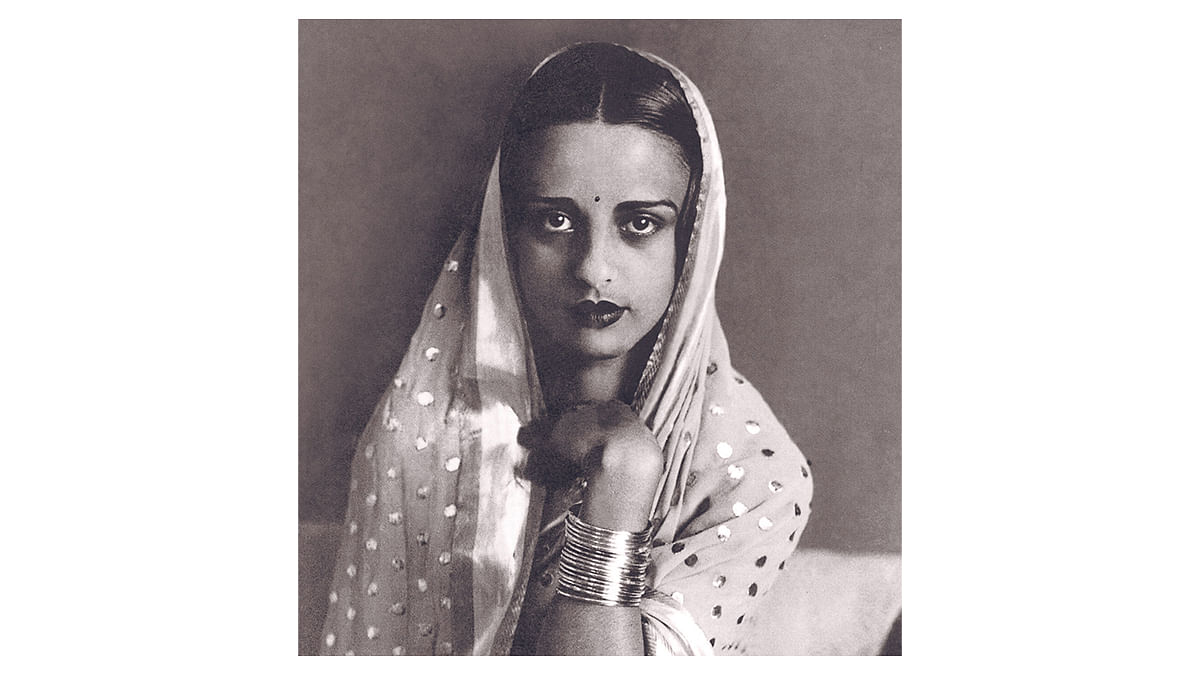

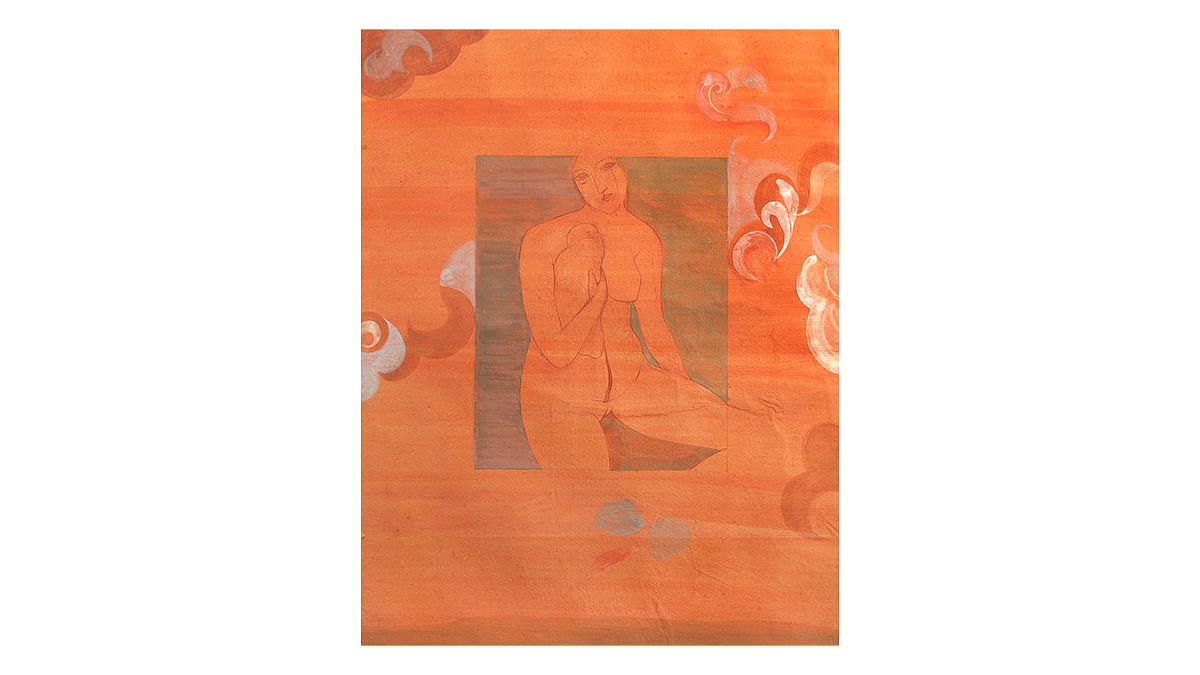

Sher-Gil, an Indo-Hungarian artist, is possibly the most celebrated woman artist of her time in the subcontinent. Trained in arts such as painting and music from an early age, she studied painting at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and is remembered for introducing the sensibilities of European modernism to Indian art discourse. Her self-portraits challenged both the male gaze and the colonial gaze prevalent in the way women were depicted in art up to that point. Upon her return to India, Sher-Gil recomposed her style to take into account the visual language of Indian artistic traditions, and shifted from depictions of her own self and interior life to those of primarily rural women — at work, in confinement, and in seclusion.

Also Read: The business of dreams — photographs from the studio of Suresh Punjabi

In the mid-1900s, women artists were often exceptional presences in artist collectives with mostly male members, and they sometimes undertook the difficult task of providing counterpoints to prevalent narratives. Among them were Arnawaz Vasudev and Anila Jaco in the Cholamandal Artists’ Village, Jaya Appasamy in the Delhi Silpi Chakra, Mrinalini Mukherjee at Shantiniketan, Anita Dube among the Kerala Radicals, and Bhanu Athaiya, the only woman in the Progressive Artists Group.

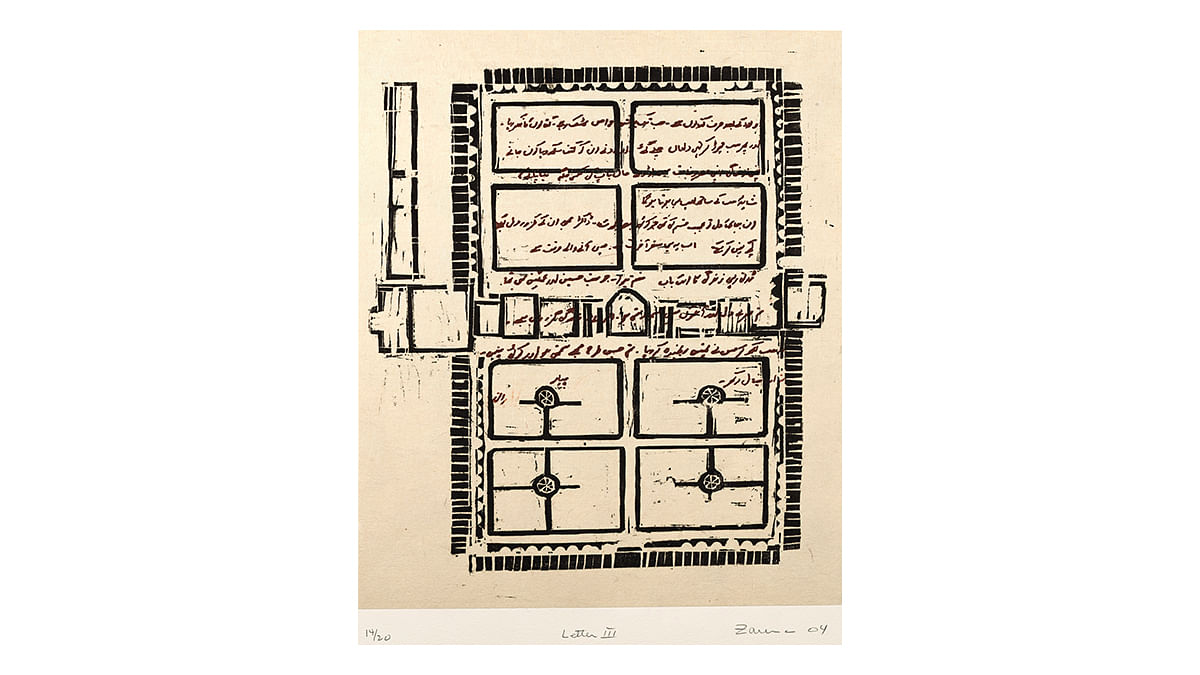

Newly independent India saw more women seeking higher education, including in the arts, both in the country and abroad. A greater volume of women could thus enter the arts and inhabit it at different levels, with and without a range of contradictions. A generation of artists that became significant in the post-independence years, especially because of their time in the West, included Nasreen Mohamedi, known for her minimalist paintings, and Zarina, known for her drawings and prints that are seen as responses to the Partition.

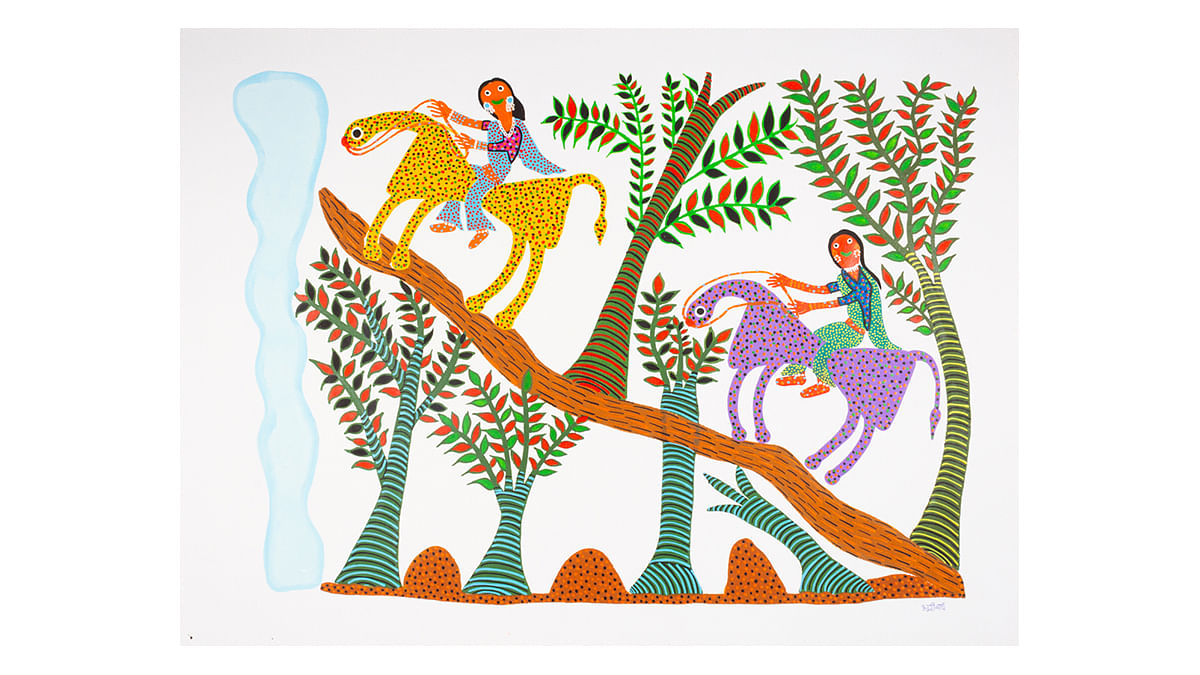

The 1980s saw the emergence of artists from indigenous communities, largely from Madhya Pradesh, including women such as Lado Bai, Bhuri Bai and Durga Bai. Working with Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal before establishing their independent careers, they participated in an art market that still consisted largely of upper class and upper caste male artists.

Women artists in the subcontinent have regularly highlighted the gendered view of certain mediums, such as watercolour, performance and video art, and reclaimed them. In the 1970s, a notable group of women artists rose to prominence for their watercolour paintings — Arpita Singh, Madhavi Parekh, Nilima Sheikh and Nalini Malani. They worked across a range of themes but were often seen as a collective following their landmark exhibition Through the Looking Glass (1979), which eventually travelled to different cities between 1987 and 1989.

Performance artists such as Rummana Hussain and Sonia Khurana used their medium to reclaim the female body from the male gaze of modernist art. They saw performance as a way to eliminate the distance and objecthood of an artwork, and it further became a gateway for them to experiment with video. In the late 1990s, several early adopters of video art — distinguished from the more male-dominated area of cinema — were women, most notably Nalini Malani, followed by artists from later generations such as Tejal Shah and Himali Singh Soin.

Photojournalism, despite being a heavily male-dominated profession, saw certain key women practitioners in the twentieth century. At the cusp of India’s independence from the British, Homai Vyarawalla became the subcontinent’s first professional female photojournalist. A graduate of the Sir JJ School of Art, Mumbai, Vyarawalla spent her early career photographing the inner world of women — on college trips, with friends, at play, at work, or on picnics — and the progressively urban life of Mumbai. After these photographs were published in magazines such as The Illustrated Weekly of India and Bombay Chronicle, she was hired by the British Information Service as a photographer, to produce and document films intended to enable British propaganda.

Alongside this work, she freelanced as a press photojournalist, and captured the twilight of the British Empire in India as well as the rebirth of India as a free nation. Another notable photographer who was witness to major political upheavals in India is Sheba Chhachhi, who is best remembered for her coverage of protest marches in the 1980s and 1990s. These decades were marked by public demonstrations and action against dowry killings and domestic violence. Her photographs document and testify to the power of feminist solidarity, and underline its magnitude.

Art and activism often went hand in hand for many women artists whose practice involved community participation, such as Navjot Altaf’s work with indigenous groups in Bastar, Chhattisgarh. The Aravani Art Project, founded in 2016 and led by transgender women, works to increase awareness of the struggles faced by transgender people and other members of the LGBTQ community in India, through graffiti and other street art in urban areas. Nevertheless, trans women continue to be under-represented in the Indian art world.

During the #MeToo movement of 2017–18, a series of accusations of sexual harassment and complicity were made against influential male figures in the Indian art industry. The movement began in 2017 in New York with Indian artist Jaishri Abichandani’s protest against a retrospective of photographer Raghubir Singh. Gaining momentum in 2018, the movement saw allegations against male artists and curators — mostly by women through anonymous posts on social media — sparking discussions on the patriarchal nature of the industry and its unregulated structure.

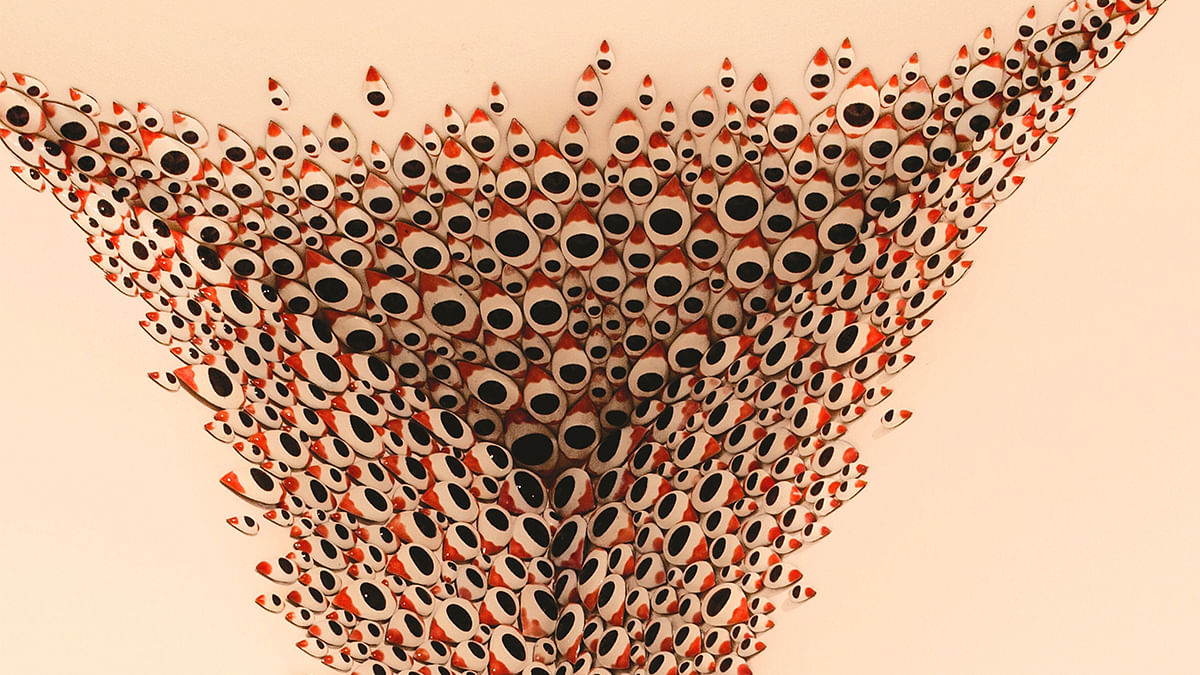

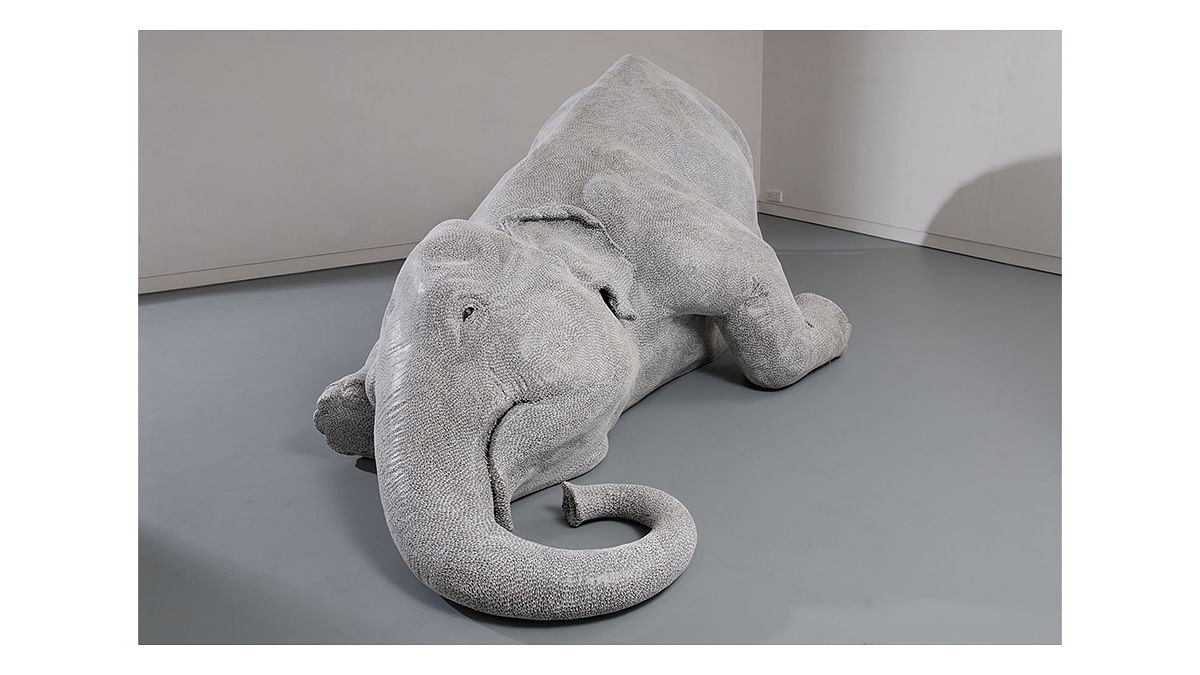

Since the 1990s, the art scene itself has been going through a sea change, with growing tendencies towards new media such as video and sound, and newer forms such as installation art, assemblage, and performance. Artists who engage with feminist issues increasingly do so in conjunction with issues of caste, social strife, globalisation, poverty, and tradition. These artists include Anju Dodiya, Bharti Kher, and Arpana Caur in sculpture and painting; Rummana Hussain, Mithu Sen, and Shilpa Gupta in multi-format conceptual art; Sheela Gowda, and Sharmila Samant in installation art; and Ketaki Sheth, Dayanita Singh, and Pushpamala N in photography.

Significant exhibitions on gender primarily featuring Indian women artists include Dispossession (1995), curated by Geeta Kapur at the Johannesburg Biennale; Woman Artists of India: A Celebration of Independence (1997) at Mills College, Oakland; Fluid Structures: Gender and Abstraction in India (2008) at Vadehra Gallery, New Delhi; Mapping Gender (2013) at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi; and In Order to Join (2013–15), curated by Swapna Tamhane and Susanne Titz, and held at various locations in Germany and Mumbai.

This article is taken from the MAP Academy‘s Encyclopedia of Art with permission.

The MAP Academy is a non-profit, open-access educational platform committed to building equitable resources for the study of art histories from South Asia. Through its freely available digital offerings—Encyclopedia of Art, Online Courses, and Stories—it encourages knowledge-building and engagement with the visual arts of the region.